Section 1 provides an overview of methods and tools for community and stakeholder engagement. It also identifies strategies for program administrators to consider in the early stages of program planning.

1.1: Community Engagement

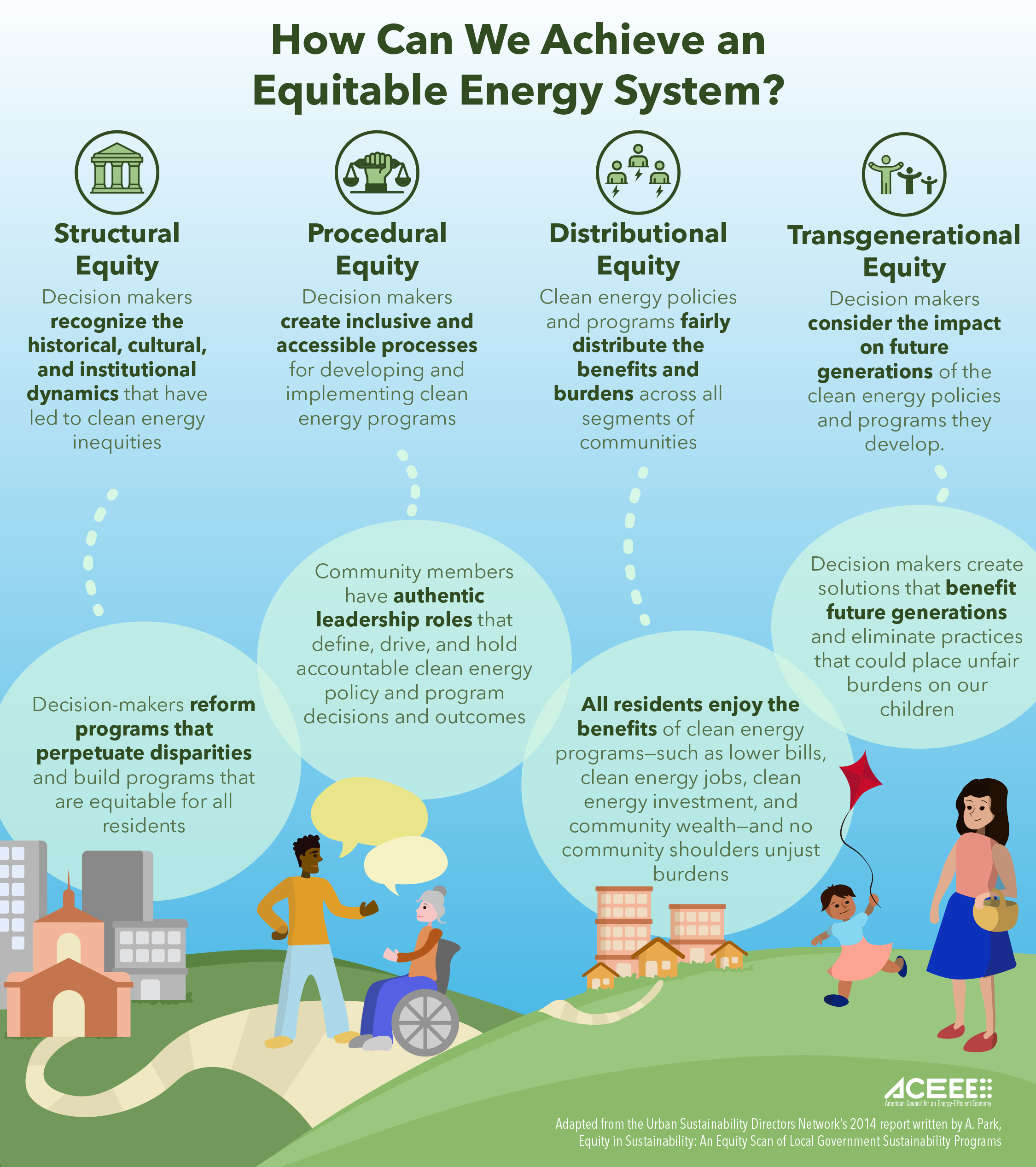

“Marginalization [is] the status quo practice of current systems that have been historically designed to exclude certain populations, namely low-income communities, communities of color, women, youth, previously incarcerated people, and queer or gender non-conforming community members. This understanding is important because if concerted efforts are not made to break-down existing barriers to participation, then by default marginalization occurs […] Whole governance and community ownership are needed to break the cycle of perpetual advocacy for basic needs that many communities find themselves in.”

Rosa González, Facilitating Power, The Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership1Rosa Gonzalez. 2019. “The Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership” movementstrategy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/The-Spectrum-of-Community-Engagement-to-Ownership.pdf.

Engaging community members is essential for designing programs that will meaningfully serve residents and bring high-priority benefits to participants and the community at large. When program administrators invest time in planning processes that center racial and social equity principles and seek broad collaboration with underserved communities, the result is more likely to be building upgrade programs that are more inviting, easier to use, better equipped to address community priorities, and capable of providing multiple benefits alongside emissions reductions. Strategies that seek to share decision making, foster collaboration, and center community priorities in programs or policies can help ensure more-equitable outcomes.2 For background on Energy Equity principles, please visit ACEEE’s Energy Equity page. ACEEE (American Council of an Energy-Efficient Economy). “Energy Equity.” aceee.org/topic/energy-equity

Community-driven planning is the process by which members of communities are empowered to define the complex challenges they face and the solutions most relevant to their unique assets and vulnerabilities.3 Rosa Gonzalez. 2017. “Community-Driven Climate Resilience Planning: A Framework.” National Association of Climate Resilience Planners. assets-global.website-files.com/65133224e95eca0de2235b3e/6572c1233211b5c31ed5ea8c_CDRP.pdf. According to the National Association of Climate Resilience Planners (NACRP), there are three essential capacities needed for this type of planning process:

- The capacity to assert a vision and articulate a set of community priorities related to that vision.

- The capacity to assess community vulnerabilities and assets and develop or select appropriate solutions based on a community’s unique experience.

- The capacity to get those solutions implemented.

Different means of engagement serve different ends. Often, community engagement is conflated with stakeholder engagement or public outreach. However, these activities are distinct and are used for different purposes.4 For more resources on Community Engagement, please see the People’s Climate Innovation Center’s Resources for Community Engagement: People’s Climate Innovation Center. “Resources for Community Engagement.” docs.google.com/document/d/1r8aUZvUh6vl-p6YuLkEajaP0Xq4Ja7cMHCgDCHpz1Bw/edit?pli=1. R2E2 employs the following definitions:

- Community engagement is designed to reach the entire community and to particularly include people who have been historically marginalized from decision making or have experienced disproportionately high burdens and/or low benefits from policies and programs.

- Stakeholder engagement is more targeted, focusing on engaging with people or organizations that have historically been recognized as having a direct stake in a policy or program and its effects.

- Public outreach is primarily meant to be informative and to broadly appeal to the public, typically without targeting specific populations. It is most often limited to one-way communication between a government and its residents and leads to minimal, if any, public input or involvement in decision making.5 Public outreach is not discussed further as part of this resource.

1.2: Community Engagement Tools

Community engagement can help building upgrade programs incorporate valuable perspectives and leadership from groups that are traditionally excluded. These groups may include:

- Community members and leaders from marginalized and frontline communities.6We define marginalized communities as those most impacted by community decision making while simultaneously being denied involvement in mainstream economic, political, cultural, and social activities and whose life outcomes are disproportionately negatively affected by social structures. Under-resourced communities have high proportions of low- and middle-income residents and generally receive a below-average quality and amount of services and financial resources from government and the private sector. Frontline communities include the populations most impacted by multiple, cumulative sources of pollution and climate impacts due to proximity to toxic factories, fossil fuel refineries, neighborhood oil drilling, freeways, and the like, often without access to clean drinking water or public investment.

- Local business owners, faith leaders, organizers, volunteers, school officials, and nonprofit leaders.

- Homeowners and renters with low incomes.7In this resource, a household is considered “low-income” if it makes less than 80% of the Area Median Income.

It is important for program administrators to emphasize accountability and transparency as part of their collaboration with communities. This can help to mitigate challenging power dynamics and repair existing mistrust. Emphasizing accountability and transparency means setting up structures to ensure:

- Clear communication about roles in partnerships among local government and community-based organizations and how community feedback will be meaningfully addressed.

- Transparent program progress reporting, no matter the degree of success.

- Fair compensation for an organization or individual’s time and expertise.

- Fulfillment of commitments.

The following section highlights three tools that can help program administrators plan community engagement activities and incorporate accountability and transparency into their programs.

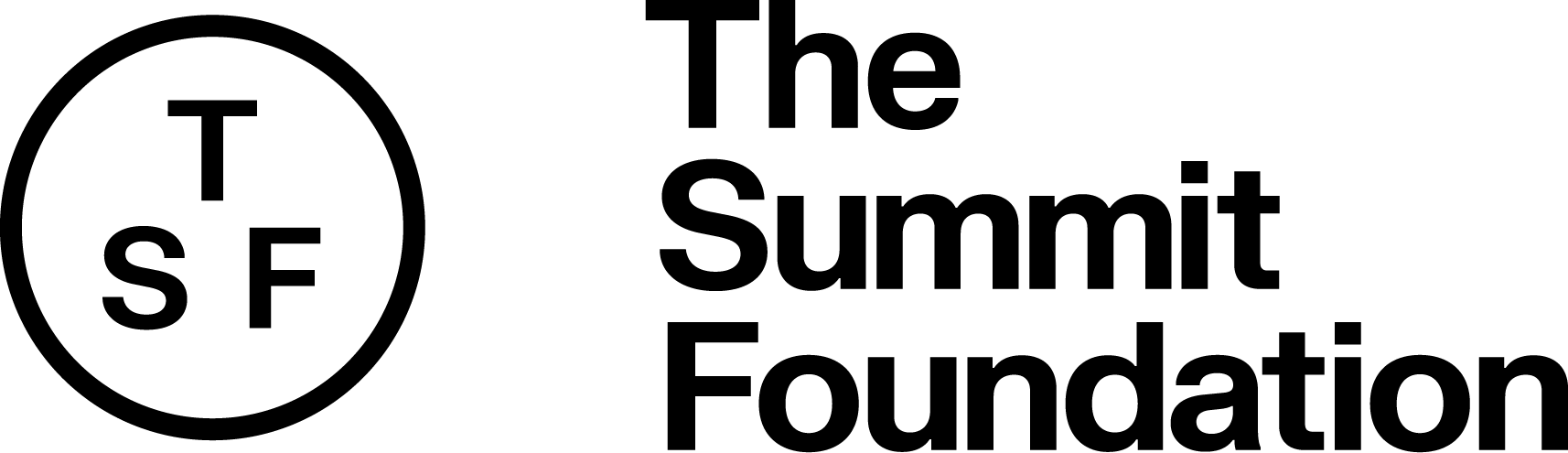

Community Engagement Tool #1 – USDN Equity Framework

The Urban Sustainability Directors Network (USDN) provides a framework that helps define the role community engagement plays in creating equitable outcomes.8 Urban Sustainability Directors Network. “Equity and Buildings: A Practical Framework for Local Government Decision Makers.” usdn.org/projects/equity-in-buildings-framework.html. This framework establishes four dimensions of equity, which include:9However, community engagement is only one part of the framework, which encompasses broader considerations. Focusing on one dimension of equity without intentionally bringing in the other three dimensions is likely to continue replicating inequitable outcomes.

Structural Equity – Decision makers recognize the historical, cultural, and institutional dynamics that have led to clean energy inequities.

Procedural Equity – Decision makers create inclusive and accessible processes for developing and implementing clean energy initiatives.

Distributional Equity – Clean energy initiatives fairly distribute the benefits and burdens across all segments of communities.

Transgenerational Equity – Decision makers consider the impact on future generations of the clean energy initiatives they develop.

Figure 1: How Can We Achieve an Equitable Energy System? 10ACEEE (American Council of an Energy-Efficient Economy). “Energy Equity.” aceee.org/topic/energy-equity.

Figure 1: How Can We Achieve an Equitable Energy System? 10ACEEE (American Council of an Energy-Efficient Economy). “Energy Equity.” aceee.org/topic/energy-equity.

Community Engagement Tool #2: The Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership.

Created by Facilitating Power, this self-assessment and planning tool demonstrates how more–impactful community engagement starts to happen toward the right side of the spectrum below.11Rosa Gonzalez. 2019. “The Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership.” movementstrategy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/The-Spectrum-of-Community-Engagement-to-Ownership.pdf.

Figure 2: The Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership

While using these tools, it is important for program administrators to keep in mind that building the relationships and trust needed for authentic community engagement takes dedicated time, resources, and ongoing commitment.

Seeking input from community members should not only take place during planning processes or when specific decisions need to be made, but throughout the entirety of an initiative. During this ongoing process, program administrators should also work to identify short-term opportunities to deliver immediate impact in the community. Successful short-term initiatives can establish a foundation of trust that can support further constructive action and long-term undertakings.

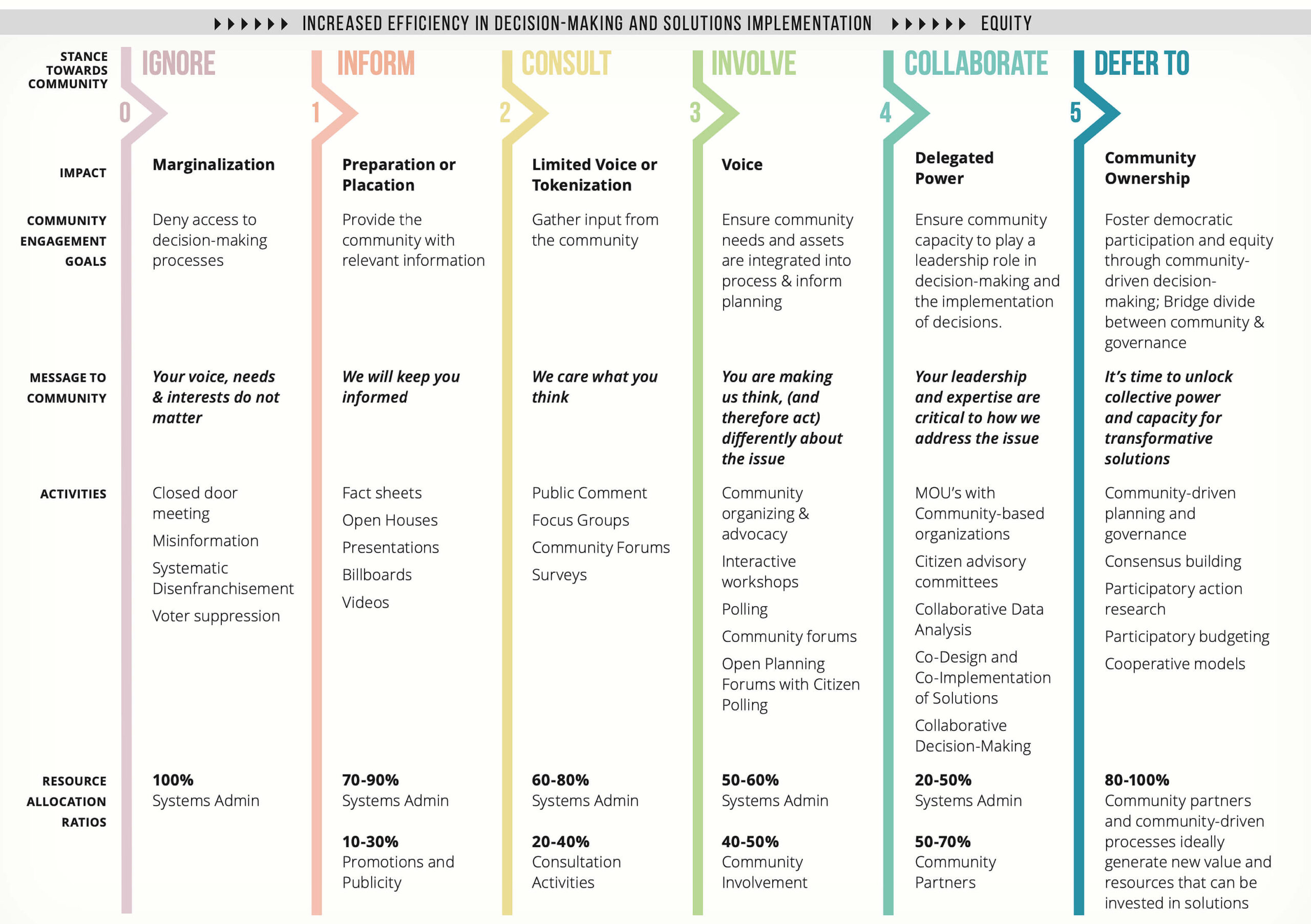

Community Engagement Tool #3: The Nexus Diagram

Relationship–building and equitable community engagement are ongoing, cyclical processes. USDN’s Nexus diagram can help program administrators understand this aspect of community engagement.

Figure 3: The Nexus Diagram12 Kristin Baja, Lindsay Ex, DeAngelo Bowden, Amy Leitch, Carmen Lopez, Jenna Witzleben, Victoria Benson, Vatic Kuumba, and Nancy Huizar. “The Nexus: Guidance for Local Governments Centering Racial Equity in Climate Planning and Practice.” usdn.org/uploads/cms/documents/_usdn_nexus_document_draft_wm_3-26-21.pdf.

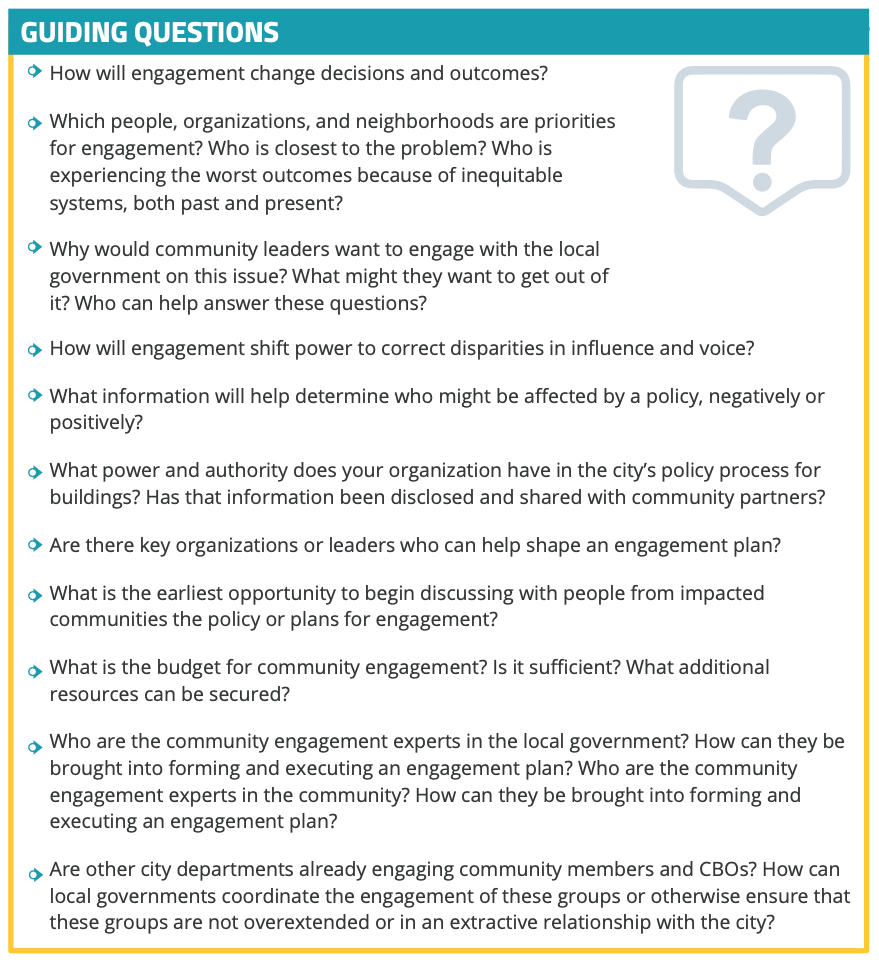

As the internal organizing stage suggests, there are numerous steps that program administrators can take to better prepare for authentic community engagement.13 Jeremy Hays, Minna Toloui, Manisha Rattu, Kathryn Wright, Denise Fairchild, Avni Jamdar, Maria Stamas, and Steve Gelb. 2021. “Equity and Buildings: A Practical Framework for Local Government Decision Makers.” These steps include:

- Identifying systemic issues and key factors (especially government policies or decisions) that have led to current racial and social disparities.

- Employing data and feedback from previous community engagement efforts to avoid engagement fatigue or burnout from frontline communities who are repeatedly engaged by different government departments or agencies.

- Building interdepartmental and intergovernmental collaborations to prepare to address multiple issues and advance multiple benefits through the work.

- Designating existing funds or procuring new funds to resource community engagement and community partners. This includes funding for translation and interpretation, participation stipends, food and childcare at meetings or engagement events, capacity-building for CBOs, etc.

- Using the “Questions to Guide Engagement” (see list below).

Figure 4: Questions to Guide Community Engagement14 Jeremy Hays, Minna Toloui, Manisha Rattu, Kathryn Wright, Denise Fairchild, Avni Jamdar, Maria Stamas, and Steve Gelb. 2021. “Equity and Buildings: A Practical Framework for Local Government Decision Makers.”

Section 1.3: Stakeholder Engagement

Program administrators should involve six key stakeholder groups in addition to community members and community-based organizations when planning a building energy upgrade program. These groups can provide valuable insights and play leadership roles in the development of programs to upgrade low- and moderate-income (LMI) housing.

These stakeholder groups include government energy and sustainability offices, affordable housing stakeholders, energy efficiency program administrators, health entities, economic inclusion and workforce stakeholders, and building energy upgrade experts and funders.

- Government energy and sustainability offices

Government energy and sustainability offices lead and help set a jurisdiction’s clean energy and climate goals.15Roxana Ayala, Ariel Drehobl, and Amanda Dewey. 2021. “Fostering Equity through Community-Led Clean Energy Strategies.” Washington, DC: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. aceee.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/u2105.pdf. 16American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE). 2023. “Energy Equity for Homeowners: Policy and Program Guide for Local Governments.” aceee.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/energy_equity_for_homeowners_guide_-_encrypt.pdf. These offices may carry out many functions, including:

- Launching or funding building energy upgrade programs.

- Referring participants to programs.

- Requiring upgrades, sometimes as a condition of receiving funding or participating in certain government programs.17Building Energy Performance Standards (BEPS) are an example of a mandatory upgrade policy. Upgrade requirements can also be attached to voluntary programs that are already funding building rehabilitation; such programs are often run by a housing agency.

- Funding or supporting community organizations doing adjacent work.

2. Affordable housing stakeholders – Housing finance agencies, public housing authorities, government housing offices, housing trust funds, syndicators, owners, renters, and funders

Publicly sponsored affordable housing activities take place across several levels of government. The federal government provides rules, regulations, and funding for major housing programs like the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), Section 8, HOME, Community Development Block Grants, USDA Rural Housing, public housing, COVID relief programs like ARPA, and the Inflation Reduction Act’s Green and Resilient Retrofit Program for Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)-assisted housing. State and local government offices also structure a wide variety of programs to fund affordable housing activities.

One critical group for program administrators to involve in stakeholder outreach is housing finance agencies (HFA). Each state has an HFA that administers affordable housing policy at the state level and allocates federal LIHTC funding. In exchange for the financing or subsidies they provide, HFAs can incentivize or mandate energy efficiency upgrades.18Dana Bartolomei. 2021. “2020 Report Update: NHT finds more states incentivized energy and water efficiency in 9 percent LIHTC properties.” energyefficiencyforall.org/updates/2020-report-update-nht-finds-more-states-incentivized-energy-and-water/.

Public housing authorities (PHA) are local government entities that own and operate public housing, funded by HUD. PHAs administer housing vouchers and utility allowances, which determine appropriate rent levels given the utility costs of residents.

Outside of HFAs and PHAs, local governments can also provide subsidies through agencies for building, preserving, or upgrading affordable housing. They also administer certain federal housing programs. More broadly, they implement zoning, issue permits, and enforce housing codes.

Tax credit syndicators, like the National Affordable Housing Trust (NAHT), are either for-profit or nonprofit entities that act as intermediaries between investors and developers that construct or preserve affordable housing. Syndicators enable investors to provide up-front cash to fund these projects in exchange for the ability to claim tax credits. These entities play several roles in building and preserving affordable housing and can also provide valuable insights for building upgrade programs.19For more information on the role of syndicators, please see this GAO resource.

Housing owners, whether for-profit or nonprofit, can also provide valuable insights to program administrators. Owners are uniquely positioned to understand the capital needs of their buildings (whether subsidized or unsubsidized), the associated costs of specific upgrades, and other opportunities and constraints.20Subsidized, public, and deed-restricted housing receive federal, state, or local funding in exchange for a use restriction. These use restrictions may limit rents or purchase prices or require occupancy by low-income residents. Subsidized housing is generally privately owned, whether by a nonprofit or for-profit owner, whereas public housing is owned by the government. 21Unsubsidized housing refers to housing that is not subsidized by any federal or state program and has no regulations on rents. Owners may seek financing to develop or rehabilitate properties, coordinate with government agencies to receive government subsidies or accept vouchers, and leverage local government programs for building upgrades. Property managers and property owner associations can also help with outreach and facilitating participation in upgrade programs.

Renter groups, such as nonprofits, renter associations, and other community-based organizations focused on housing issues, can provide a valuable perspective on community upgrade opportunities, issues affecting tenants, and avenues for improving living conditions in rental housing.

Program administrators will also likely need to coordinate with affordable housing funders, which provide capital for the construction or rehabilitation of housing. Funders include Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI), banks, and other lenders.22CDFIs are mission-driven financial institutions that create economic opportunity for individuals and small businesses, high-quality affordable housing, and essential community services in the United States. Four types of institutions are included in the definition of a CDFI: CD banks, CD credit unions, CD loan funds (most of which are nonprofit), and CD venture capital funds. CDFIs may be certified by the CDFI Fund. See: Office of Comptroller of the Currency. “Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) and Community Development (CD) Bank Resource Directory.” occ.gov/topics/consumers-and-communities/community-affairs/resource-directories/cdfi-and-cd-bank/index-cdfi-and-cd-bank-resource-directory.html.

3. Energy efficiency program administrators

The administrators of the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) and the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) are state agencies, though often not the same state agency. Weatherization reduces energy costs for households with low incomes by increasing the energy efficiency of homes.23The topic of weatherization is covered in more detail in Section 2.2. LIHEAP provides bill assistance to address energy bill shortfalls and emergencies. A LIHEAP administrator might be able to refer participants for upgrade program participation or offer insight into cost-burdened communities. Both WAP and LIHEAP are often implemented by community action agencies (CAA), which can provide helpful insights regarding on-the-ground upgrade needs and barriers to implementation.

Energy efficiency program administrators are typically utilities, using funds provided by ratepayers, but can also be a state agency or nonprofit organization using ratepayer or other funds. These entities are another valuable stakeholder group to include in engagement. In the case of WAP and utility programs, there may be an opportunity to achieve economies of scale by building on existing offerings.

These existing programs often have limitations on what upgrades they cover, which creates coverage or funding gaps that administrators may need to fill with their building upgrade programs. For example, WAP must spend its entire federal allocation (including a recent federal cash influx) on an annual timeline, but the program can serve only a fraction of eligible households each year.24The IIJA included $3.5 billion for WAP to be spent over several years. For more information, see ACEEE‘s report ”Home Energy Upgrades Incentives: Programs in the Inflation Reduction Act and other recent federal laws.” Moreover, despite the recent boost in funding, federal rules mean that agencies can spend only $8,000 per home:25Weatherization Assistance Program: Office of State and Community Energy Programs. “Weatherization Assistance Program.” energy.gov/scep/weatherization-assistance-program.

This means that programs must still leverage outside funding for more-comprehensive upgrades. WAP also defers many homes from the program because they are not able to allocate sufficient funding to meet health and safety needs that must be addressed before weatherization can occur. Also, many community action agencies focus their efforts on one- to four-unit properties, even though properties of five or more units are also eligible.

These limitations or gaps—a program’s comprehensiveness, and whether it covers health and safety measures or multifamily buildings—may present opportunities for discussion and partnership with your state WAP administrator or local implementer.

Importantly, utility-administered energy efficiency programs may have constraints, such as cost-effectiveness tests, that create gaps in their programs. These might result in the inability to serve certain building types (e.g. only single-family homes, only master-metered multifamily buildings), offering only direct-install measures such as LED bulbs, or not offering electrification measures. Community stakeholders and intervenors in public utility commission proceedings (e.g., clean energy advocates, public utility commission staff) can be another helpful source for learning about utility program gaps and shortcomings.

4. Health entities

Marginalized communities are especially susceptible to in-home health and safety hazards, and homes with health hazards are often energy inefficient. 26Hayes, S., M. MacPherson, C. Gerbode, and L. Ross. 2022. “Pathways to Healthy, Affordable, Decarbonized Housing: A State Scorecard.” Washington, DC: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. www.aceee.org/research-report/h2201. 27ACEEE (American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy). “Healthy Buildings.” aceee.org/topic/indoor-air-quality.Building upgrades can reduce exposure to mold, asbestos, and moisture, improve indoor air quality, and make indoor environments more comfortable for residents.28For a more detailed discussion of the relationship between home health hazards and energy inefficiency, please see Section 3.2.

There are a variety of entities working to improve public health and reduce healthcare costs that may be interested in supporting programs to improve energy efficiency.

These entities include:

- Healthcare providers and hospitals.

- Community health clinics.

- Managed care organizations (such as HMOs or PPOs).

- State and local public health departments.

- Locally administered health programs.

Some of these entities may already be running healthy home programs to remove asthma triggers, lead, and other hazards from homes. Specifically, healthcare providers, hospitals, and managed care organizations are motivated to reduce healthcare costs and may provide in-home health interventions to that end. For such programs, administrators may be municipal, nonprofit, or private entities.

Health initiatives and healthy homes programs may present opportunities to build on existing efforts to install home health upgrades or provide health services.29ACEEE (American Council of an Energy-Efficient Economy). “Healthy Buildings.” aceee.org/topic/indoor-air-quality.

There are several locally administered health programs, such as the federal CHIP Health Services Initiative, that conduct in-home lead abatement, modify homes to remove asthma triggers, and work to reduce federal healthcare spending via clean energy upgrades. These programs can be administered through state or county health agencies and may also present partnership opportunities for building upgrade program administrators. For more information on health and safety stakeholders, see Section 3.2: Health and safety.

5. Economic inclusion and workforce stakeholders

Building energy upgrade programs can also create numerous economic benefits and high-road, equitable opportunities for local workers and businesses connected to disadvantaged communities.30High-road employment is typically understood as workforce development and applies to individuals. The high-road approach focuses on workforce opportunities that increase access to jobs for people who need them most and others who have been historically excluded from career-track, family-sustaining employment, and improving the quality of jobs that allow workers to be economically self-sufficient, upwardly mobile, and safe and healthy while at work. A high-road job market also encourages competition based on the quality of work rather than exclusively the cost.See: Barr Foundation. “An Assessment of the Clean Energy Workforce in New England.” barrfoundation.org/reports/building-new-england-clean-enegy-workforce. Focusing on economic inclusion can help align upgrade work with a jurisdiction’s other priorities, including driving economic recovery, increasing racial equity, delivering community benefits, and repairing harm from past government actions.31 Economic inclusion is a process that includes high-road employment and contracting opportunities and improved access to those opportunities for historically marginalized people and communities.

Key stakeholders for workforce development include:

- High schools, trade schools, community colleges, and universities, which can offer training for the workforce.

- City or county workforce development agencies, which may run programs for incumbent workers to upskill or provide services (e.g. career exploration, job placement) to opportunity youth.32 This term refers to low-income 16 to 24-year-olds who have left high school or are underemployed.

- YouthBuild or JobCorps program administrators, which run programs for opportunity youth funded by the U.S. Department of Labor. YouthBuild programs are run by CBOs or others named above and primarily build homes for low-income households. JobCorps administrators run JobCorps centers.

- Employers and contractors, which hire new entrants and other job seekers, upskill the existing workforce, and provide training.

The business support ecosystem includes:

- Apprenticeship program administrators such as unions, labor-management organizations, business associations, and community colleges.

- Small Business Development Centers, which are locally administered centers funded by the Small Business Administration that provide technical assistance, coaching, and access to loans related to business planning.

- Business associations and chambers of commerce, which include MBE/WBE (Minority Business Enterprise/Woman Business Enterprise) and specific ethnic business associations (e.g., Hispanic Chamber of Commerce).

Partnership with such entities might establish goals and accountability via community benefits agreements with the community. For example, agreements might set targets and require reporting on hiring workers from disadvantaged communities. They can also create opportunities for new workers or those who have been left out of the labor force to receive training (e.g., via apprenticeship programs or community colleges). For more information on economic inclusion and workforce stakeholders, see Section 3.4: Workforce development and economic inclusion.

6. Building energy upgrade experts and funders

Energy, decarbonization, and building stakeholders often help design and implement building energy upgrade programs. Technical experts can advise on building needs, appropriate technologies, costs, and benefits, including how to ensure that electrification results in stable or lower bills for low-income residents. Energy service companies (ESCO) operate performance-based programs and can manage and finance large upgrade projects. Clean energy advocacy organizations can provide valuable insight into the gaps and shortcomings of existing programs, emerging program models, and best practices. Green banks, where they exist, can combine public and private funds to speed up the adoption of commercially available technologies. Organizations that advise on building science can also provide valuable feedback on the structure of upgrade programs.33 Some of these organizations, for example, are part of the Relay Network and the Clean and Equitable Buildings Collaborative.

Click here to access Actions and Best Practices for Section 1

- 1Rosa Gonzalez. 2019. “The Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership” movementstrategy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/The-Spectrum-of-Community-Engagement-to-Ownership.pdf.

- 2For background on Energy Equity principles, please visit ACEEE’s Energy Equity page. ACEEE (American Council of an Energy-Efficient Economy). “Energy Equity.” aceee.org/topic/energy-equity

- 3Rosa Gonzalez. 2017. “Community-Driven Climate Resilience Planning: A Framework.” National Association of Climate Resilience Planners. assets-global.website-files.com/65133224e95eca0de2235b3e/6572c1233211b5c31ed5ea8c_CDRP.pdf.

- 4For more resources on Community Engagement, please see the People’s Climate Innovation Center’s Resources for Community Engagement: People’s Climate Innovation Center. “Resources for Community Engagement.” docs.google.com/document/d/1r8aUZvUh6vl-p6YuLkEajaP0Xq4Ja7cMHCgDCHpz1Bw/edit?pli=1.

- 5Public outreach is not discussed further as part of this resource.

- 6We define marginalized communities as those most impacted by community decision making while simultaneously being denied involvement in mainstream economic, political, cultural, and social activities and whose life outcomes are disproportionately negatively affected by social structures. Under-resourced communities have high proportions of low- and middle-income residents and generally receive a below-average quality and amount of services and financial resources from government and the private sector. Frontline communities include the populations most impacted by multiple, cumulative sources of pollution and climate impacts due to proximity to toxic factories, fossil fuel refineries, neighborhood oil drilling, freeways, and the like, often without access to clean drinking water or public investment.

- 7In this resource, a household is considered “low-income” if it makes less than 80% of the Area Median Income.

- 8Urban Sustainability Directors Network. “Equity and Buildings: A Practical Framework for Local Government Decision Makers.” usdn.org/projects/equity-in-buildings-framework.html.

- 9However, community engagement is only one part of the framework, which encompasses broader considerations. Focusing on one dimension of equity without intentionally bringing in the other three dimensions is likely to continue replicating inequitable outcomes.

- 10ACEEE (American Council of an Energy-Efficient Economy). “Energy Equity.” aceee.org/topic/energy-equity.

- 11Rosa Gonzalez. 2019. “The Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership.” movementstrategy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/The-Spectrum-of-Community-Engagement-to-Ownership.pdf.

- 12Kristin Baja, Lindsay Ex, DeAngelo Bowden, Amy Leitch, Carmen Lopez, Jenna Witzleben, Victoria Benson, Vatic Kuumba, and Nancy Huizar. “The Nexus: Guidance for Local Governments Centering Racial Equity in Climate Planning and Practice.” usdn.org/uploads/cms/documents/_usdn_nexus_document_draft_wm_3-26-21.pdf.

- 13Jeremy Hays, Minna Toloui, Manisha Rattu, Kathryn Wright, Denise Fairchild, Avni Jamdar, Maria Stamas, and Steve Gelb. 2021. “Equity and Buildings: A Practical Framework for Local Government Decision Makers.”

- 14Jeremy Hays, Minna Toloui, Manisha Rattu, Kathryn Wright, Denise Fairchild, Avni Jamdar, Maria Stamas, and Steve Gelb. 2021. “Equity and Buildings: A Practical Framework for Local Government Decision Makers.”

- 15Roxana Ayala, Ariel Drehobl, and Amanda Dewey. 2021. “Fostering Equity through Community-Led Clean Energy Strategies.” Washington, DC: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. aceee.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/u2105.pdf.

- 16American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE). 2023. “Energy Equity for Homeowners: Policy and Program Guide for Local Governments.” aceee.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/energy_equity_for_homeowners_guide_-_encrypt.pdf.

- 17Building Energy Performance Standards (BEPS) are an example of a mandatory upgrade policy. Upgrade requirements can also be attached to voluntary programs that are already funding building rehabilitation; such programs are often run by a housing agency.

- 18Dana Bartolomei. 2021. “2020 Report Update: NHT finds more states incentivized energy and water efficiency in 9 percent LIHTC properties.” energyefficiencyforall.org/updates/2020-report-update-nht-finds-more-states-incentivized-energy-and-water/.

- 19

- 20Subsidized, public, and deed-restricted housing receive federal, state, or local funding in exchange for a use restriction. These use restrictions may limit rents or purchase prices or require occupancy by low-income residents. Subsidized housing is generally privately owned, whether by a nonprofit or for-profit owner, whereas public housing is owned by the government.

- 21Unsubsidized housing refers to housing that is not subsidized by any federal or state program and has no regulations on rents.

- 22CDFIs are mission-driven financial institutions that create economic opportunity for individuals and small businesses, high-quality affordable housing, and essential community services in the United States. Four types of institutions are included in the definition of a CDFI: CD banks, CD credit unions, CD loan funds (most of which are nonprofit), and CD venture capital funds. CDFIs may be certified by the CDFI Fund. See: Office of Comptroller of the Currency. “Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) and Community Development (CD) Bank Resource Directory.” occ.gov/topics/consumers-and-communities/community-affairs/resource-directories/cdfi-and-cd-bank/index-cdfi-and-cd-bank-resource-directory.html.

- 23The topic of weatherization is covered in more detail in Section 2.2.

- 24The IIJA included $3.5 billion for WAP to be spent over several years. For more information, see ACEEE‘s report ”Home Energy Upgrades Incentives: Programs in the Inflation Reduction Act and other recent federal laws.”

- 25Weatherization Assistance Program: Office of State and Community Energy Programs. “Weatherization Assistance Program.” energy.gov/scep/weatherization-assistance-program.

- 26Hayes, S., M. MacPherson, C. Gerbode, and L. Ross. 2022. “Pathways to Healthy, Affordable, Decarbonized Housing: A State Scorecard.” Washington, DC: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. www.aceee.org/research-report/h2201.

- 27ACEEE (American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy). “Healthy Buildings.” aceee.org/topic/indoor-air-quality.

- 28For a more detailed discussion of the relationship between home health hazards and energy inefficiency, please see Section 3.2.

- 29ACEEE (American Council of an Energy-Efficient Economy). “Healthy Buildings.” aceee.org/topic/indoor-air-quality.

- 30High-road employment is typically understood as workforce development and applies to individuals. The high-road approach focuses on workforce opportunities that increase access to jobs for people who need them most and others who have been historically excluded from career-track, family-sustaining employment, and improving the quality of jobs that allow workers to be economically self-sufficient, upwardly mobile, and safe and healthy while at work. A high-road job market also encourages competition based on the quality of work rather than exclusively the cost.See: Barr Foundation. “An Assessment of the Clean Energy Workforce in New England.” barrfoundation.org/reports/building-new-england-clean-enegy-workforce.

- 31Economic inclusion is a process that includes high-road employment and contracting opportunities and improved access to those opportunities for historically marginalized people and communities.

- 32This term refers to low-income 16 to 24-year-olds who have left high school or are underemployed.

- 33Some of these organizations, for example, are part of the Relay Network and the Clean and Equitable Buildings Collaborative.