Section 2 provides an overview of important data sources to use while identifying program focus areas. It also explains elements of building upgrade scopes of work and specific considerations for affordable housing.

2.1: Using Data to Identify Program Focus Areas

Along with undertaking effective community and stakeholder engagement, using data to understand how complex inequities shape the realities of communities is a powerful step for planning programs or policies that seek to address and repair previous harm. Developing an effective and equitable building energy upgrade program requires both quantitative and qualitative data.

There are numerous data sources that can be used to understand trends or conditions in a geographic area, such as the American Housing Survey (AHS), the U.S. Census, and existing local studies and planning documents. However, these data may fall short of fully reflecting the daily experiences of community members. Using datasets alongside community input to design and inform policies and programs is essential to ameliorating inequities in LMI communities.1 NB: In many instances, it is not possible to receive input from communities to complement existing data sources before building trust with communities that have experienced significant harms from decision makers. This often takes significant resources to accomplish and will be context dependent. 2Ford, TN and Goger, A. 2021. “The Value of Qualitative Data for Advancing Equity in Policy.” The Brookings Institution Blog, August 14. brookings.edu/articles/value-of-qualitative-data-for-advancing-equity-in-policy/.

There are many supplementary data tools available that focus specifically on data related to environmental justice metrics. These tools can help decision makers direct investments to underserved communities. For example, to help achieve the goals of Justice40, the federal government has created several tools, including:3The federal government has made it a goal that 40% of the overall benefits of certain federal investments flow to disadvantaged communities that are marginalized, underserved, and overburdened by pollution. See: The White House. ” Justice40: A Whole-of-Government Initiative.” whitehouse.gov/environmentaljustice/justice40.

- The Climate & Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST), which includes visual data layers in a map to highlight communities that face significant environmental and housing burdens.

- EPA’s environmental justice screening and mapping tool, EJScreen.

- DOE’s LEAD tool, which helps users understand housing and energy characteristics for low- and moderate-income households.

Several state and local governments have also created similar tools using local data. However, it is important to note that these data sources do not always capture local realities, community priorities, fluid conditions, and other circumstances that could impact the success of a building upgrade initiative. For example, CEJST currently does not use race as an indicator in the tool to identify disadvantaged communities, despite race being clearly correlated with many of the indicators in the tool.4 Rajat Shrestha, Sujata Rajpurohit and Devashree Saha. 2023. World Resources Institute. CEQ’s Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool Needs to Consider How Burdens Add Up. Washington, D.C. 5 Sadasivam, N and Aldern, C. 2022. Grist. The White House excluded race from its environmental justice tool. We put it back in. grist.org/equity/climate-and-economic-justice-screening-tool-race/

2.2 Building Upgrade and Decarbonization Strategies

Building energy upgrades enhance energy efficiency in existing buildings. They can significantly reduce building energy use, playing a critical role in addressing climate change and improving the quality of homes and buildings. Scopes of work with deep retrofits can reduce a home’s energy use by 58% to 79% and its emissions by 32% to 56%, depending on the home’s age and the regional climate where the home is located.6 Deep retrofits are whole-home projects that incorporate more–extensive envelope and equipment upgrades with the goal of achieving whole-home energy savings of 50% or more. Deep energy reduction projects expand on the range of measures targeted in retrofit projects to include behavioral measures and a more comprehensive set of end uses with the goal of achieving at least a 50% reduction in energy use. See: Jennifer Amann, Rohini Srivastava, and Nick Henner. 2021. “Pathways for Deep Energy Use Reductions and Decarbonizations in Homes.” Washington, DC: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. Aceee.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/b2103.pdf. 7 Ben Somberg. 2021. “Report: Deep Retrofits Can Halve Homes’ Energy Use and Emissions.” aceee.org/press-release/2021/12/report-deep-retrofits-can-halve-homes-energy-use-and-emissions.

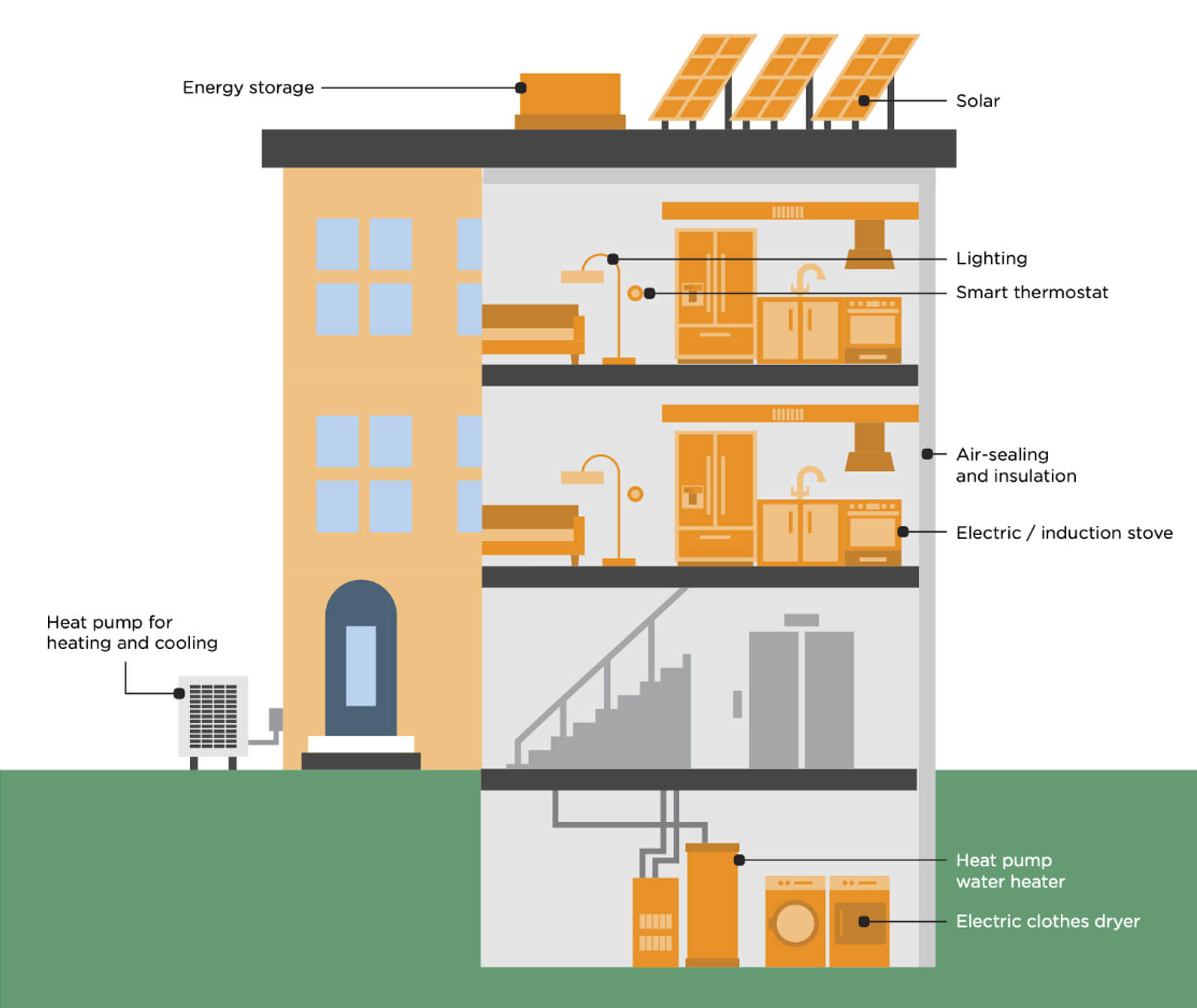

A building energy upgrade scope of work may include:

- Adding new technology to an older building system (focusing on the improved energy performance of the building).8 A building system is a combination of equipment, operations, controls, accessories, and means of interconnection that use energy to perform a specific function. Examples include heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC), water heating, lighting, thermal envelope, and miscellaneous electrical load systems. See: Associated Cooling Services. 2020. “What is HVAC and How is it Different from Air Conditioning?” acsuk.org/what-is-hvac-and-how-is-it-different-from-air-conditioning/

- Making the building more efficient through the tune up, repair, or replacement of an existing system or systems (including plumbing HVAC systems).9HVAC is responsible for heating and cooling a building. It’s also a source of proper ventilation, allowing for moisture to escape. Better Buildings, U.S. Department of Energy. “Building Envelope” betterbuildingssolutioncenter.energy.gov/building-envelope.

- Improvements to the envelope (including weatherization).10 The envelope, which includes the walls, windows, roof, and foundation, forms the primary thermal barrier between the interior and exterior environments.

Weatherization typically involves efficiency improvements to a building’s envelope through insulation, air sealing, or window upgrades. Weatherization can help address health issues like asthma, uncomfortable or dangerous indoor temperatures, and indoor air pollution. Strengthening a building’s envelope can block pollutants from entering a house and regulate indoor temperatures, thereby reducing exposure to outside air pollution and extreme heat and cold.11 Sara Hayes and Christine Gerbode. “Session 1: Providing Health Services as Part of Residential Energy Saving Programs” aceee.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/Session%201%20Presentation%20Deck.pdf. Energy upgrades that improve a building’s ventilation and filtration systems can also mitigate asthma and other respiratory illnesses.

Comprehensive building energy upgrades are a whole-building approach to address deficiencies in the building envelope and complete necessary upgrades to major systems. These upgrades include a suite of measures that typically require engineers, contractors, or special tradespeople to install. Comprehensive upgrades are undertaken to improve building energy efficiency and achieve savings larger than those possible from the installation of isolated measures.

Decarbonization encompasses strategies for reducing building-related carbon emissions. Key approaches include energy efficiency upgrades, replacing fossil fuel equipment with efficient electric equipment (electrification) and distributed generation (e.g., solar).12 Electrification refers to fully or partially switching from technologies that directly use fossil fuel to those that use electricity. 13 Distributed generation refers to a variety of technologies that generate electricity at or near where it will be used, such as solar panels and combined heat and power. See: The Alliance to Save Energy. “Building Systems Efficiency.” WBDG, December 7, 2018. https://www.wbdg.org/resources/building-systems-efficiency Beyond reduced greenhouse gas emissions, other benefits may include improved indoor air quality, reduced utility bills, and greater ease of maintenance.

Many techniques can be used to upgrade the envelope, heating and cooling systems, water heating system, lighting, and other aspects of a home’s energy equipment.

Building envelope upgrades

- These upgrades ensure that a building can retain heat in the winter and keep it out in the summer, reducing HVAC load. They include improvements to air sealing, duct sealing, and insulation in the walls, attic, and foundation. They can also include replacing windows, doors, installing secondary windows, and weatherization measures.14HVAC and water heating are the most significant contributors to household energy consumption, and the most significant energy savings benefits come from making these systems more efficient, as well as strengthening a building’s envelope. See: “U.S. Energy Information Administration – EIA – Independent Statistics and Analysis.” Electricity use in homes – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/use-of-energy/electricity-use-in-homes.php.

Heat pumps for heating and cooling15 Heat pumps are systems that use electricity to transfer heat. During the heating season, heat pumps move heat from the cool outdoors into hotter indoor environments. During the cooling season, heat pumps move heat from the hotter indoor environment into the outdoors. There are many types of heat pumps connected by ducts (air-to-air, water source, and geothermal), as well as ductless heat pump systems. Geothermal heat pumps operate similarly to air-source heat pumps, but they move heat between the indoor environment and the ground. Geothermal heat pumps are able to take advantage of ground temperatures, which are more consistent than air temperatures. U.S. Department of Energy. “Heat Pump Systems.” https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/heat-pump-systems U.S. Department of Energy. “Heat Pump Hot Water Heaters.” https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/heat-pump-water-heaters.

- Instead of generating heat through electric resistance or combusting fossil fuels, these systems transfer heat from one place to another, much like refrigerators and air conditioners do.16 An electric resistance heater converts the electrical energy a device consumes to the heat supplied to a space; electric resistance heat can be supplied by centralized forced-air electric furnaces or by heaters in each room. Room heaters can consist of electric baseboard heaters, electric wall heaters, electric radiant heat, or electric space heaters. They can be used for both heating and cooling. These systems are more efficient than standard electric resistance, gas or oil heating systems. Installing geothermal heat pumps can reduce household energy use by as much as 80% and installing air-source heat pumps (ASHP) can reduce household energy use by as much as 65%.17 U.S. Department of Energy. “Heat Pump Systems.” energy.gov/energysaver/heat-pump-systems.

Heat pump water heaters (HPWH)

- Heat pumps can also be used to heat water. Importantly, HPWHs have some unique installation considerations, including location, required space, and planning for potential noise from the system.

Lighting and appliances

- Lighting upgrades often involve converting a building to be fully lit by LED lighting. These upgrades can also include sensors and controls that regulate lighting and home appliances, including refrigerators, stoves, and heat pump/hybrid dryers. 18 Efficient stoves include induction stoves, a special type of electric cooktop that uses induction technology. This technology generates energy from an electromagnetic field below the glass cooktop surface, which transfers current directly to magnetic cookware. This causes the cookware to heat up. Currently, there is no specific ENERGY STAR certification or DOE standard for induction stoves, just for electric stoves generally. As of the writing of this report, available electric resistance and induction stoves have comparable performance. U.S. Department of Energy. “Gas and Electric Ovens, Stoves, and Ranges” energy.gov/energysaver/gas-and-electric-ovens-stoves-and-ranges. 19 A heat pump dryer works as a closed loop system by heating the air used to remove moisture from the clothes and then reusing it once the moisture is removed. Rather than releasing warm, humid air through a dryer vent to the exterior of the home as a conventional dryer does, a heat pump dryer sends it through an evaporator to remove the moisture without losing too much heat. EPA’s ENERGY STAR Program certifies energy-efficient lighting and appliances.

Electric infrastructure

- Electric infrastructure upgrades can include higher-capacity or smarter electrical panels and circuit splitters for load shifting and prioritization to limit simultaneous power draw.20Smart electrical panels give users more control over the electrical circuits in their home. See: New ‘smart panels’ give homeowners real-time control of their energy use – WSJ. https://www.wsj.com/articles/smart-panels-home-improvement-energy-9544da4a.21Load shifting is the ability to move electricity consumption from one time period to another (e.g., from peak hours to off-peak hours). Slipstream. 2020. Load shifting: The measures that can save energy and carbon together. slipstreaminc.org/research/load-shifting-measures. These changes can help facilitate increased plug loads.22 Plug load refers to energy used by equipment that is plugged into an outlet. GSA. “Plug Load Nuggets.” https://www.gsa.gov/governmentwide-initiatives/federal-highperformance-green-buildings/resource-library/energy-water/plug-loads/plug-load-nuggets.

Figure 1: Examples of decarbonization measures in a multifamily building23Elevate

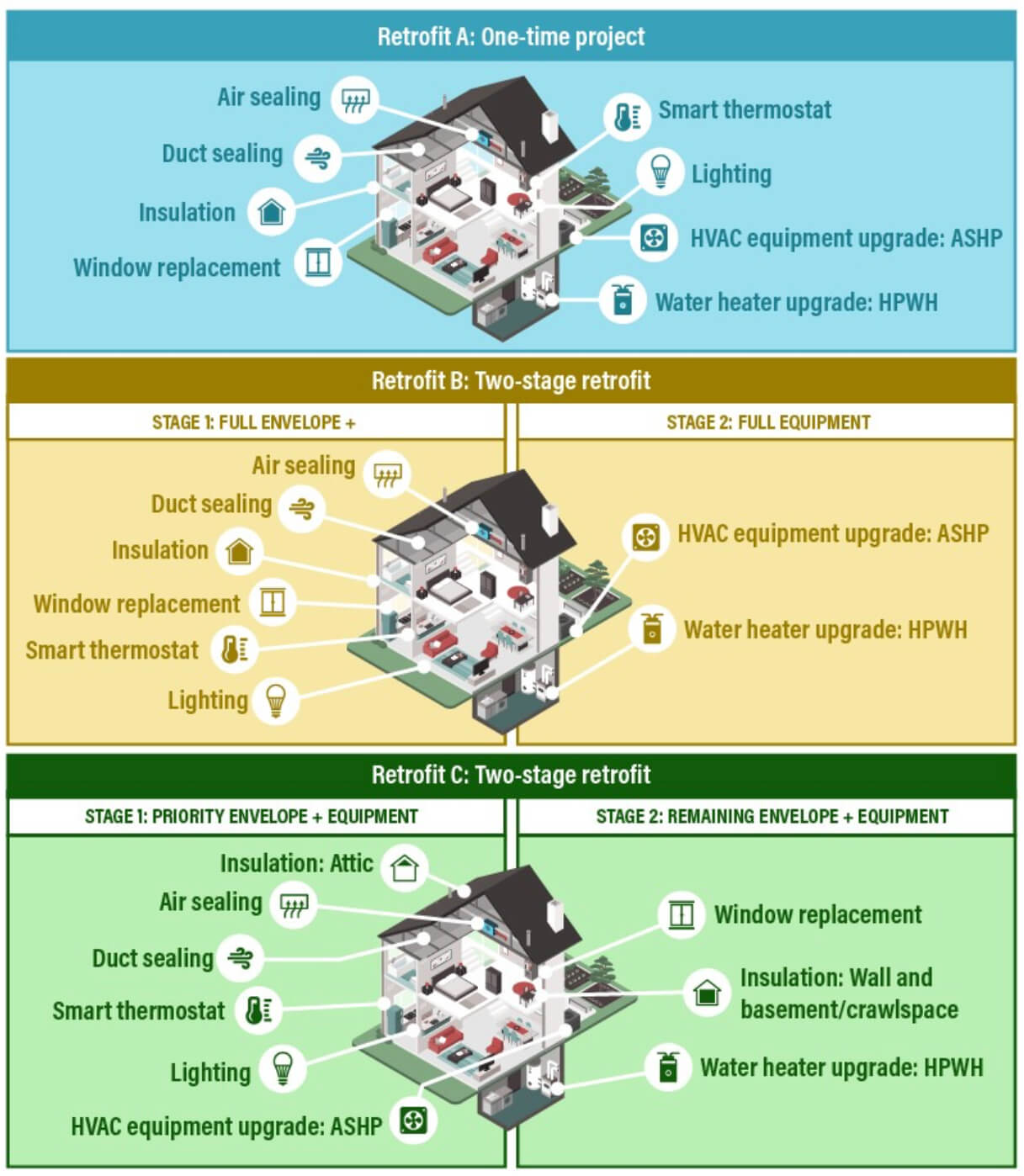

Energy upgrades that reduce total building energy loads and costs are often the basis for efficient electrification upgrades made to support decarbonization.24Efficient electrification is a term for replacing direct fossil fuel use (e.g., propane, heating oil, gasoline) with electricity in a way that reduces energy use. For more information, See: Steven Nadel, 2023. “The United States Can Electrify Most Fossil Fuel Use: Here Is What Needs to Happen to Make This Possible.” Washington, DC: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. https://www.aceee.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/the_united_states_can_electrify_most_fossil_fuel_use_encrypt.pdf. While the sequencing of comprehensive upgrades may vary widely depending on the building’s needs, three examples of typical sequencing are shown in the figure below.

Figure 2: Examples of Retrofit Sequencing25Amann, J., R. Srivastava, and N. Henner. 2021. Pathways to Residential Deep Energy Reductions and Decarbonization. Washington, DC: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. https://www.aceee.org/research-report/b2103

Section 2.3: Considerations for Low- and Moderate-Income Housing

Affordable housing can improve the quality of life and costs of living for low-income renters, while benefiting homeowners and rental property owners through energy cost savings, lower operation and maintenance costs, and better renter retention. However, because affordable housing is typically older and more likely to be in areas prone to environmental hazards, it is often less energy efficient and more susceptible to high energy costs.26 Abigail Corso, Pat Coleman, John Viner, Claire Oleksiak. 2022. “Making Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing More Efficient: Outreach to Upgrade.” elevatenp.org/wp-content/uploads/NOAH-Programs-Elevate-NEI-Summer-Study-Presentation.pdf. 27Frederick J. Eggers. 2017. “Characteristics of HUD-Assisted Renters and Their Units in 2013.” huduser.gov/portal/publications/Characteristics-HUD-Assisted.html. This can make designing building upgrade programs to serve affordable housing a unique challenge.

Housing is generally considered affordable when housing costs, including utility costs, are less than 30% of a household’s income. Households that pay more than 30% of income towards these costs are considered cost-burdened. For most subsidized or public affordable housing, households are considered eligible based on how their household income compares to the Area Median Income (AMI), the midpoint income for their region. A household is often considered “low-income” if it earns less than 80% of AMI. Cost-burdened low-income households have fewer resources for basic needs, such as healthcare, food, and childcare. These households are also more likely to experience housing instability, overcrowding, and eviction.28 HUD Fair Market Rents and Income Limits. See: HUD’s Office of Policy Development and Research. 2023. “Income Limits.” Huduser.gov/portal/datasets/il.html.

For most of the 20th century, government agencies and private financial institutions reinforced segregation and restricted people of color from building wealth through discriminatory housing and finance policies and exclusionary zoning laws. Redlining is a particularly relevant example of how racist policies led to divestment and reduced opportunity for wealth generation for communities of color. Redlining was a practice endorsed by the U.S. government to designate areas on maps as good or bad investments.29 Jake Blugmart. 2017. “How Redlining Segregated Philadelphia.” Next City Blog, December 8. https://nextcity.org/features/redlining-race-philadelphia-segregation.30 Many sources on housing segregation and redlining point to the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) as a driver of redlining and discriminatory housing practices. However, several scholars have pointed out the more significant role of federal agencies such as the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in redlining. For more information on the research examining each entity‘s role, please see Blugmart (2017). Jake Blugmart. 2017. “How Redlining Segregated Philadelphia.” Next City Blog, December 8. nextcity.org/features/redlining-race-philadelphia-segregation. Areas that had high concentrations of communities of color were labeled as areas of bad investment, effectively leading to the continued disinvestment of entire neighborhoods.31 Andre M. Perry and David Harshbarger. 2019. “America’s Formerly Redlined Neighborhoods Have Changed, and So Must Solutions to Rectify Them” brookings.edu/articles/americas-formerly-redlines-areas-changed-so-must-solutions Today, the amount, location, availability, and quality of housing stock, along with access to resources in underinvested communities, can often trace their roots back to these policies.

Affordable housing typologies

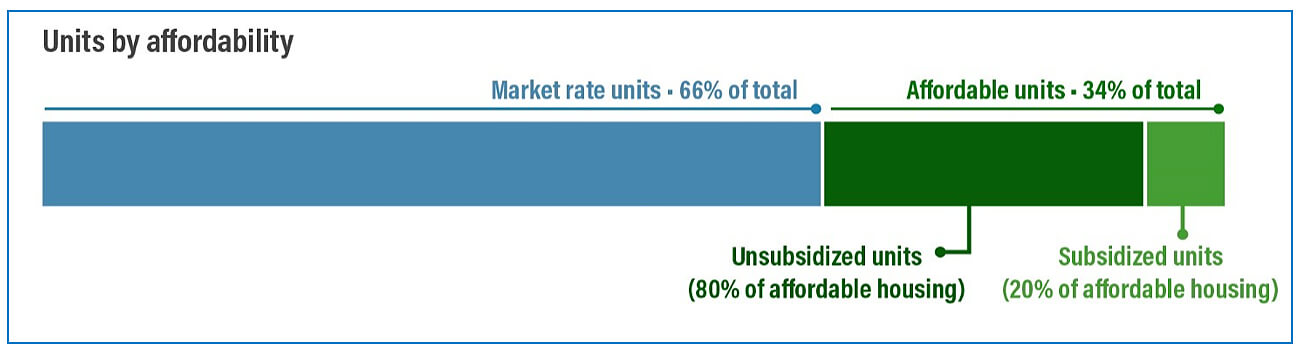

Only 34% of all housing units in the United States are considered affordable for low- and moderate-income households. Only 4% of all housing units (20% of the affordable units) are subsidized through affordable housing finance agencies, public housing authorities, deed restrictions, inclusionary zoning, and/or rent control laws.32 Abigail Corso, Pat Coleman, Claire Oleksiak, and Dane John Viner. “Making Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing More Efficient: Outreach to Upgrade.” elevatenp.org/wp-content/uploads/Making-Naturally-Occurring-Affordable-Housing-More-Efficient.pdf.

The other 30% (80% of the affordable units) are unsubsidized but still affordable to households making under 80% AMI.33 This subset of the market is sometimes called naturally occurring affordable housing (NOAH) and may include owner-occupied housing or unsubsidized and non-restricted rental housing. Unsubsidized affordable housing often faces challenges related to building age, deferred maintenance, and high utility costs, and can be in areas at a high risk for natural disasters.34Abigail Corso, Pat Coleman, Claire Oleksiak, and Dane John Viner. “Making Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing More Efficient: Outreach to Upgrade.” elevatenp.org/wp-content/uploads/Making-Naturally-Occurring-Affordable-Housing-More-Efficient.pdf

Figure 3: Housing units by affordability level and subsidy status in the United States35 HR&A advisors.

When planning or implementing building energy upgrade programs, it is helpful to keep these key distinctions and market segments in mind; different types of affordable housing may require different program approaches. In addition to differences between unsubsidized and subsidized affordable housing, single-family and multifamily housing often have very different needs and are best served by different program design features, timelines, and funding/financing options. Engaging local affordable housing stakeholders can help program administrators better understand specific program design components that will be attractive to different housing types and owners.

For unsubsidized rental housing, program administrators will need to navigate the risk that energy upgrades will spur property owners to increase rents, either to pay back the cost of the upgrades or to capitalize on their buildings’ newly updated features. For subsidized housing, program administrators will need to design their programs around these properties’ complex financing and regulatory constraints, which are generally overseen by the state housing finance agency.

The unique challenges of implementing energy upgrades in affordable housing

There are numerous challenges specific to implementing building upgrades in affordable housing.

- Due in part to a history of disinvestment and racial injustice, affordable housing stock tends to have more significant health, safety, and structural repair needs, which can make the cost of upgrade projects more expensive.36 Jarrah, Alexander, Emily Garfunkel, and David Ribeiro. 2024. Nobody Left Behind: Preliminary Review of Strategies to Support Affordable Housing Compliance with Building Performance Standards. Washington, DC: ACEEE. www.aceee.org/research-report/b2401

- Owners and financiers may be concerned about high project costs and a lack of clarity about the return on investments through energy cost savings.

- Renters and advocates may be concerned about life disruption during building upgrades and resident displacement.

Anticipating the effect that building upgrades might have on renters’ housing costs (including rent) requires a holistic understanding of the local housing market and demand for upgraded rental homes, the incentives building owners can use for each type of housing, and how low- to moderate-income renters in these housing types might experience cost shifts. In the case of electrification upgrades, for example, if a renter pays the electric bill and the building owner pays the gas bill, the cost of heating (or cooling) may shift to the renter. If the owner pays the electric bill, the cost of building upgrades may be passed on to the renter in the form of rent increases.

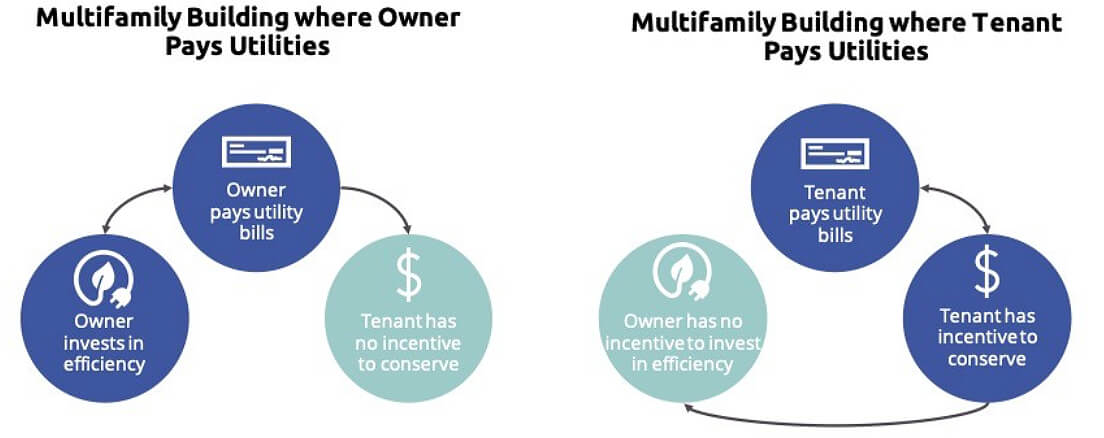

In fact, one of the greatest challenges to making the case for upgrades in all rental housing (both affordable and market rate) is the diffusion of decision making among different stakeholders. For instance, if a renter pays for their utilities, an owner does not have an incentive to invest in efficiency (also known as the split incentive). Conversely, if an owner pays for utility costs, a renter may not have an incentive to keep energy costs down.

Figure 4: The split incentive37HR&A Advisors.

Interventions must be designed to overcome these challenges. For instance, a program can seek to cover as much of the upgrade cost as possible, so that the rental property owner does not experience pressure to raise rents to recoup their investment. Alternatively, a program that provides conditional capital funding support for building upgrades to reduce energy consumption can also incentivize owners to improve renter quality of life and agree to certain rent or energy cost restrictions. Examples of such interventions are included in the list of actions for this section. Preventing increased household energy costs due to electrification should be a primary focus of program administrators.

It is important to note that, in most situations, efficient building electrification will reduce overall bills for households.38 Yim, E., and S. Subramanian. 2023. Equity and Electrification-Driven Rate Policy Options. Washington, DC: ACEEE. aceee.org/white-paper/2023/09/equity-and-electrification-driven-rate-policy-options. While pairing electrification scopes with weatherization and distributed generation can help prevent increased household costs, program administrators should also get involved in conversations with local utilities, ratepayer advocates, and other stakeholders related to rate-setting for low-income households, or more cutting-edge approaches to neighborhood-level energy savings, such as neighborhood-scale building decarbonization.39 Mark Kresowik. 2024. “Heat Pump Programs Can’t Keep Leaving Low-Income Households Behind.” ACEEE Blog, February 12. aceee.org/blog-post/2024/02/heat-pump-programs-cant-keep-leaving-low-income-households-behind. 40 Kristin George Bagdanov, Claire Halbrook, and Amy Rider. 2023 “Neighborhood Scale: The Future of Building Decarbonization.” buildingdecarb.org/ resource/neighborhoodscale. While weighing these challenges, administrators should seek to maximize positive outcomes identified as priorities during community engagement.41 For additional information about the benefits of efficient building electrification, please see the findings from a recent study in Joule: “News Release: Benefits of Heat Pumps Detailed in New NREL Report.” NREL. https://www.nrel.gov/news/press/2024/benefits-of-heat-pumps-detailed-in-new-nrel-report.html.

Click here to access Actions and Best Practices for Section 2

- 1NB: In many instances, it is not possible to receive input from communities to complement existing data sources before building trust with communities that have experienced significant harms from decision makers. This often takes significant resources to accomplish and will be context dependent.

- 2Ford, TN and Goger, A. 2021. “The Value of Qualitative Data for Advancing Equity in Policy.” The Brookings Institution Blog, August 14. brookings.edu/articles/value-of-qualitative-data-for-advancing-equity-in-policy/.

- 3The federal government has made it a goal that 40% of the overall benefits of certain federal investments flow to disadvantaged communities that are marginalized, underserved, and overburdened by pollution. See: The White House. ” Justice40: A Whole-of-Government Initiative.” whitehouse.gov/environmentaljustice/justice40.

- 4Rajat Shrestha, Sujata Rajpurohit and Devashree Saha. 2023. World Resources Institute. CEQ’s Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool Needs to Consider How Burdens Add Up. Washington, D.C.

- 5Sadasivam, N and Aldern, C. 2022. Grist. The White House excluded race from its environmental justice tool. We put it back in. grist.org/equity/climate-and-economic-justice-screening-tool-race/

- 6Deep retrofits are whole-home projects that incorporate more–extensive envelope and equipment upgrades with the goal of achieving whole-home energy savings of 50% or more. Deep energy reduction projects expand on the range of measures targeted in retrofit projects to include behavioral measures and a more comprehensive set of end uses with the goal of achieving at least a 50% reduction in energy use. See: Jennifer Amann, Rohini Srivastava, and Nick Henner. 2021. “Pathways for Deep Energy Use Reductions and Decarbonizations in Homes.” Washington, DC: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. Aceee.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/b2103.pdf.

- 7Ben Somberg. 2021. “Report: Deep Retrofits Can Halve Homes’ Energy Use and Emissions.” aceee.org/press-release/2021/12/report-deep-retrofits-can-halve-homes-energy-use-and-emissions.

- 8A building system is a combination of equipment, operations, controls, accessories, and means of interconnection that use energy to perform a specific function. Examples include heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC), water heating, lighting, thermal envelope, and miscellaneous electrical load systems. See: Associated Cooling Services. 2020. “What is HVAC and How is it Different from Air Conditioning?” acsuk.org/what-is-hvac-and-how-is-it-different-from-air-conditioning/

- 9HVAC is responsible for heating and cooling a building. It’s also a source of proper ventilation, allowing for moisture to escape. Better Buildings, U.S. Department of Energy. “Building Envelope” betterbuildingssolutioncenter.energy.gov/building-envelope.

- 10The envelope, which includes the walls, windows, roof, and foundation, forms the primary thermal barrier between the interior and exterior environments.

- 11Sara Hayes and Christine Gerbode. “Session 1: Providing Health Services as Part of Residential Energy Saving Programs” aceee.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/Session%201%20Presentation%20Deck.pdf.

- 12Electrification refers to fully or partially switching from technologies that directly use fossil fuel to those that use electricity.

- 13Distributed generation refers to a variety of technologies that generate electricity at or near where it will be used, such as solar panels and combined heat and power. See: The Alliance to Save Energy. “Building Systems Efficiency.” WBDG, December 7, 2018. https://www.wbdg.org/resources/building-systems-efficiency

- 14HVAC and water heating are the most significant contributors to household energy consumption, and the most significant energy savings benefits come from making these systems more efficient, as well as strengthening a building’s envelope. See: “U.S. Energy Information Administration – EIA – Independent Statistics and Analysis.” Electricity use in homes – U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/use-of-energy/electricity-use-in-homes.php.

- 15Heat pumps are systems that use electricity to transfer heat. During the heating season, heat pumps move heat from the cool outdoors into hotter indoor environments. During the cooling season, heat pumps move heat from the hotter indoor environment into the outdoors. There are many types of heat pumps connected by ducts (air-to-air, water source, and geothermal), as well as ductless heat pump systems. Geothermal heat pumps operate similarly to air-source heat pumps, but they move heat between the indoor environment and the ground. Geothermal heat pumps are able to take advantage of ground temperatures, which are more consistent than air temperatures. U.S. Department of Energy. “Heat Pump Systems.” https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/heat-pump-systems U.S. Department of Energy. “Heat Pump Hot Water Heaters.” https://www.energy.gov/energysaver/heat-pump-water-heaters.

- 16An electric resistance heater converts the electrical energy a device consumes to the heat supplied to a space; electric resistance heat can be supplied by centralized forced-air electric furnaces or by heaters in each room. Room heaters can consist of electric baseboard heaters, electric wall heaters, electric radiant heat, or electric space heaters.

- 17U.S. Department of Energy. “Heat Pump Systems.” energy.gov/energysaver/heat-pump-systems.

- 18Efficient stoves include induction stoves, a special type of electric cooktop that uses induction technology. This technology generates energy from an electromagnetic field below the glass cooktop surface, which transfers current directly to magnetic cookware. This causes the cookware to heat up. Currently, there is no specific ENERGY STAR certification or DOE standard for induction stoves, just for electric stoves generally. As of the writing of this report, available electric resistance and induction stoves have comparable performance. U.S. Department of Energy. “Gas and Electric Ovens, Stoves, and Ranges” energy.gov/energysaver/gas-and-electric-ovens-stoves-and-ranges.

- 19A heat pump dryer works as a closed loop system by heating the air used to remove moisture from the clothes and then reusing it once the moisture is removed. Rather than releasing warm, humid air through a dryer vent to the exterior of the home as a conventional dryer does, a heat pump dryer sends it through an evaporator to remove the moisture without losing too much heat.

- 20Smart electrical panels give users more control over the electrical circuits in their home. See: New ‘smart panels’ give homeowners real-time control of their energy use – WSJ. https://www.wsj.com/articles/smart-panels-home-improvement-energy-9544da4a.

- 21Load shifting is the ability to move electricity consumption from one time period to another (e.g., from peak hours to off-peak hours). Slipstream. 2020. Load shifting: The measures that can save energy and carbon together. slipstreaminc.org/research/load-shifting-measures.

- 22Plug load refers to energy used by equipment that is plugged into an outlet. GSA. “Plug Load Nuggets.” https://www.gsa.gov/governmentwide-initiatives/federal-highperformance-green-buildings/resource-library/energy-water/plug-loads/plug-load-nuggets.

- 23Elevate

- 24Efficient electrification is a term for replacing direct fossil fuel use (e.g., propane, heating oil, gasoline) with electricity in a way that reduces energy use. For more information, See: Steven Nadel, 2023. “The United States Can Electrify Most Fossil Fuel Use: Here Is What Needs to Happen to Make This Possible.” Washington, DC: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. https://www.aceee.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/the_united_states_can_electrify_most_fossil_fuel_use_encrypt.pdf.

- 25Amann, J., R. Srivastava, and N. Henner. 2021. Pathways to Residential Deep Energy Reductions and Decarbonization. Washington, DC: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. https://www.aceee.org/research-report/b2103

- 26Abigail Corso, Pat Coleman, John Viner, Claire Oleksiak. 2022. “Making Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing More Efficient: Outreach to Upgrade.” elevatenp.org/wp-content/uploads/NOAH-Programs-Elevate-NEI-Summer-Study-Presentation.pdf.

- 27Frederick J. Eggers. 2017. “Characteristics of HUD-Assisted Renters and Their Units in 2013.” huduser.gov/portal/publications/Characteristics-HUD-Assisted.html.

- 28HUD Fair Market Rents and Income Limits. See: HUD’s Office of Policy Development and Research. 2023. “Income Limits.” Huduser.gov/portal/datasets/il.html.

- 29Jake Blugmart. 2017. “How Redlining Segregated Philadelphia.” Next City Blog, December 8. https://nextcity.org/features/redlining-race-philadelphia-segregation.

- 30Many sources on housing segregation and redlining point to the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) as a driver of redlining and discriminatory housing practices. However, several scholars have pointed out the more significant role of federal agencies such as the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) in redlining. For more information on the research examining each entity‘s role, please see Blugmart (2017). Jake Blugmart. 2017. “How Redlining Segregated Philadelphia.” Next City Blog, December 8. nextcity.org/features/redlining-race-philadelphia-segregation.

- 31Andre M. Perry and David Harshbarger. 2019. “America’s Formerly Redlined Neighborhoods Have Changed, and So Must Solutions to Rectify Them” brookings.edu/articles/americas-formerly-redlines-areas-changed-so-must-solutions

- 32Abigail Corso, Pat Coleman, Claire Oleksiak, and Dane John Viner. “Making Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing More Efficient: Outreach to Upgrade.” elevatenp.org/wp-content/uploads/Making-Naturally-Occurring-Affordable-Housing-More-Efficient.pdf.

- 33This subset of the market is sometimes called naturally occurring affordable housing (NOAH) and may include owner-occupied housing or unsubsidized and non-restricted rental housing.

- 34Abigail Corso, Pat Coleman, Claire Oleksiak, and Dane John Viner. “Making Naturally Occurring Affordable Housing More Efficient: Outreach to Upgrade.” elevatenp.org/wp-content/uploads/Making-Naturally-Occurring-Affordable-Housing-More-Efficient.pdf

- 35HR&A advisors.

- 36Jarrah, Alexander, Emily Garfunkel, and David Ribeiro. 2024. Nobody Left Behind: Preliminary Review of Strategies to Support Affordable Housing Compliance with Building Performance Standards. Washington, DC: ACEEE. www.aceee.org/research-report/b2401

- 37HR&A Advisors.

- 38Yim, E., and S. Subramanian. 2023. Equity and Electrification-Driven Rate Policy Options. Washington, DC: ACEEE. aceee.org/white-paper/2023/09/equity-and-electrification-driven-rate-policy-options.

- 39Mark Kresowik. 2024. “Heat Pump Programs Can’t Keep Leaving Low-Income Households Behind.” ACEEE Blog, February 12. aceee.org/blog-post/2024/02/heat-pump-programs-cant-keep-leaving-low-income-households-behind.

- 40Kristin George Bagdanov, Claire Halbrook, and Amy Rider. 2023 “Neighborhood Scale: The Future of Building Decarbonization.” buildingdecarb.org/ resource/neighborhoodscale.

- 41For additional information about the benefits of efficient building electrification, please see the findings from a recent study in Joule: “News Release: Benefits of Heat Pumps Detailed in New NREL Report.” NREL. https://www.nrel.gov/news/press/2024/benefits-of-heat-pumps-detailed-in-new-nrel-report.html.