Section 3 focuses on the initial steps required to implement an upgrade program, key partnerships, accessing various funding sources, and incorporating health and safety measures and workforce development opportunities into building energy upgrade programs.

3.1: Program Implementation and Partnerships

Offering an easy point of entry and individualized guidance for building decision makers through every step of the process can help program administrators reach residents who have historically been underserved by energy efficiency offerings.

Building upgrades can reduce high energy burdens and improve living conditions for low-income households, but they can also negatively impact residents if not designed well. As discussed elsewhere in this Playbook, program strategies to mitigate displacement and unaffordable costs are necessary to ensure residents can stay in their homes and benefit from greater affordability, improved health, and other potential benefits. Ensuring high-quality upgrades is necessary for residents’ satisfaction, and evaluating a program’s progress toward its goals is beneficial for continuous improvement and accountability to the community.

R2E2 recommends that the process of standing up an easy-to-use program begins by developing a program framework. A program framework involves creating a strategy that outlines community-specific details that will inform program design and implementation, including goals and outcomes for the program, the audience served, and services needed for your target audience. The steps to developing a framework include:

1. Convene an initial meeting of the program design team. This team can consist of stakeholders, community representatives, and other early partners. This meeting can be used to discuss the results of your initial landscape analysis and community engagement, with the goal of developing a program framework.

a. Identify a timeline and next steps. For each major step in the process, all necessary assumptions, external factors, intended inputs and outputs or impacts should be defined.

b. Identify gaps in knowledge. If gaps in knowledge or experience are revealed during the meeting, the team should review the landscape analysis and other sources to see what resources exist to fill the gap. These resources may be individuals, best practice guides, case studies, etc.

2. Make the framework accessible. Once the initial draft of the framework is complete, it should be translated into a representation that community members can easily engage with. Just as in the initial community engagement, events should be scheduled to share the framework and solicit community members’ input.1 For more information on how to approach equitable community engagement, see Section 1.1. The community input should then be discussed among the design team and where feasible, adjustments should be made to the framework to integrate the feedback. This process may need to be repeated until consensus is achieved.

3. Assign teams to refine the framework. The responsibility for further researching and designing components of the framework (e.g., outreach, intake, assessment, funding/financing) should be assigned to team members or sub-groups with regular check-ins scheduled to ensure that the early work of standing up a program stays aligned.

4. Create a program manual. The framework should be memorialized in a program manual that will be the resource for implementing and administering the program. How long this process takes before a program is launched depends on the size and scope of the program, the capacity of team members, and any external forces at play, such as funding deadlines. It is important to remember that the work of program design does not end when the program is launched; the team should be ready to change and continually improve the program to best fit community needs, and to compensate community ambassadors, advisors, and liaisons for their continued feedback and participation during this process.

3.2: Health and Safety

Buildings can have a large impact on occupant health, especially considering that Americans on average spend about 90% of their time indoors.3 Christopher Bloom. 2023. “June Is National Healthy Homes Month” NCHS Blog, May 31. nchh.org/2023/05/june-is-national-healthy-homes-month-2023/. The presence of mold, pests, and bacterial agents inside a home can result in various respiratory illnesses, and these effects often disproportionately impact marginalized communities. Asthma, for instance, is a common respiratory illness that disproportionately affects Black Americans, American Indians, Alaska Natives, and people living below the federal poverty threshold.4 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2023. ” Most Recent National Asthma Data” cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm.

While most households can benefit from upgrades that simultaneously improve a building’s energy performance and address health hazards, communities of color and low-income households could reap the most benefits from healthy housing energy upgrades. Compared to white, higher-income households, these households are more likely to live in inefficient, inadequate housing that leads to high energy bills and poor health.5 Hayes, S., M. MacPherson, C. Gerbode, and L. Ross. 2022. Pathways to Healthy, Affordable, Decarbonized Housing: A State Scorecard. Washington, DC: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. aceee.org/research-report/h2201.

Many homes—often those that are least efficient—may need significant health and safety repairs before weatherization and other energy efficiency upgrades can happen.6 Jonathan Wilson and Ellen Tohn. 2010-2011. “Healthy Housing Opportunities During Weatherization Work.” Golden, Colorado: National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Nrel.gov/docs/fy11osti/49947.pdf. 7 Bratburd, Jennifer. 2021 “Increasing Access to Energy Efficiency: Options for Improving Weatherization Assistance.” MOST Policy Initiative. mostpolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/MOST_WX_report_2021.pdf. Often, if these repairs are not made, households may not be able to access critical funds, such as those provided by the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP).8 E4TheFuture. 2022. “Weatherization Barriers Toolkit” e4thefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/E4-EFG_Weatherization-Barriers-Toolkit-4-7-2022.pdf. WAP deferrals highlight the necessity of prioritizing health and safety repairs in building upgrade programs.9 WAP deferral is a widespread problem. A study from National Public Radio (NPR) found that in some jurisdictions, up to 60% of properties that are financially eligible for WAP are deferred from the program due to significant repair needs.

Once homes are ready for weatherization, they can receive upgrades that can mitigate indoor air quality hazards and remove harmful pollutants or unhealthy building materials. Residents can then enjoy lower energy bills, more comfortable living conditions, and better respiratory health.

However, program administrators should take care that upgrades do not introduce toxic building materials into homes; insulation and sealants are common sources of toxins that can be harmful to the health of building occupants, installers, and manufacturing workers, but healthier options are available.10 Veena Singla et. al. 2018. “Making Affordable Multifamily Housing More Energy Efficient: A Guide to Healthier Upgrade Materials” energyefficiencyforall.org/resources/making-affordable-multifamily-housing-more-energy-efficient-guide-healthier-upgrade/. 11 For more information on healthy building materials, see resources from Habitable, including resources on insulation product guidance and sealant product guidance.

As discussed in Section 1, health-oriented programs offer additional opportunities for braiding and blending funding. Health funding can come from the Center for Disease Control (CDC), the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and various environmental health grants.12 See Hayes and Christine Gerbode. 2020. “Braiding Energy and Health Funding for In-Home Programs: Federal Funding Opportunities” Washington, DC: ACEEE. aceee.org/research-report/h2002. For more information on healthy buildings, please see ACEEE’s Healthy Buildings page.

3.3: Accessing Funding Sources

Finding and properly leveraging and braiding funding sources for building energy upgrade programs for low- and moderate-income housing is a prerequisite for successful implementation.

There are many sources of funding available, ranging from federal, state, and local government sources to philanthropies, nonprofits, utilities, and private entities. Drawing on multiple sources can help program administrators scale up building retrofits by offering additional measures, covering more of the upgrade costs, or reaching more homes. Providing substantial financial incentives for homeowners and rental property owners—or even covering the entire upgrade cost—can lead to higher program enrollment.

When considering various funding sources for a program, it is important to define and distinguish between the methods of braiding and blending funds. While braiding preserves the individual identities and requirements associated with the various funding sources, blending combines sources into one pot. Braiding is the dominant strategy because, although it can involve more-complex reporting, it is often easier to implement because of statutory requirements on funding sources. Using braiding and blending funding techniques, program administrators can effectively combine multiple sources to fund upgrade initiatives.

The process of braiding funds can be described in a few simple steps (although there is no one-size-fits-all model):

- Identify available funding streams.

- Identify eligible populations and compare requirements.

- Align requirements of funding streams.

- Develop shared goals and a plan for collaboration.

- Develop governance structures to support collaboration.

- Identify and address gaps and barriers to participation in program implementation.

Funding for upgrade programs—for the measures themselves and the administrative costs—can come in many forms: incentives, discounts, rebates, loans, grants, prizes, and in-kind services. For each of these funding sources, there are numerous considerations to keep in mind, including the following:

- Incentives, discounts, and rebates can help offset project implementation costs but do not cover full costs.

- While loans often require repayment, grants and prizes do not need to be paid back.

- Grants may have strict requirements for eligibility and reporting.

- In-kind services are similar to technical assistance services that can be used to help run and implement a program.

The federal government is an important source of funding for efficiency upgrades. Programs that support energy efficiency upgrades are typically administrated by several key federal agencies: DOE, EPA, HUD, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), among others.

Funding from these agencies can take various forms. For example, the IRS provides tax credits or other tax incentives for certain energy efficiency projects.13 One problem with tax credits, however, is that unless they are refundable they are less likely to be helpful to low-income families; a household must have a tax liability in order for it to be reduced. Other agencies typically provide grants or low-cost financing to states, local governments, businesses, or directly to households, depending on the program.

Grants can be discretionary (also known as competitive funding) or based on a formula (also known as formula funding).14 Formula grants are funding programs that an applicant does not compete for, though they must submit an application and meet other specified requirements. They ensure that designated recipients will receive funds and are usually administered and managed by state administering agencies. National Institute of Food and Agriculture. “Types of Federal Assistance” nifa.usda.gov/about-nifa/what-we-do/types-federal-assistance#Competitive. Discretionary grants are issued competitively, meaning eligible entities will compete to win funding for a specific project or program. Formula grants are allocated to state or local governments by way of a predetermined eligibility formula, so they are effectively guaranteed should the state or local government choose to pursue the funding.

Recent federal legislation, including the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) and the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) (also known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law), has made billions of dollars available for climate investments, including funding for building energy efficiency upgrades.15 For more information on the IRA, please see ACEEE‘s policy brief on Home Energy Upgrade Incentives. Ungar, L., and S. Nadel. 2022. Home Energy Upgrade Incentives: Programs in the Inflation Reduction Act and Other Recent Federal Laws. Washington, DC: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. aceee.org/policy-brief/2022/09/home-energy-upgrade-incentives-programs-inflation-reduction-act-and-other.

One very large source of funding for building upgrades will originate from EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF). In April 2024, the agency announced three awardees for the National Clean Investment Fund ($14 billion) and five awardees of the Clean Communities Investment Accelerator ($6 billion). These awardees will establish a national clean financing network that will finance climate and clean energy projects, including building upgrades.

Energy efficiency funding is available across a variety of federal programs, as highlighted in the table below.

For more information on various federal programs, please visit R2E2’s Resources page, which includes an FAQ on federal funding, a resource on federal efficiency and electrification rebate programs, and a resource on HUD’s Green and Resilient Retrofit Program.

Figure 1: Federal funding for energy efficiency

Figure 1: Federal funding for energy efficiency

State and local government funding opportunities are also available for various building types, including affordable housing. These opportunities vary more by geography, so it is incumbent on program administrators to explore funding opportunities specific to their state or locality. The state housing finance agency can be a good place to start exploring these opportunities.

There are also numerous non-governmental funding sources. Utility programs, for instance, can be useful for reducing upfront costs through rebates, although these program offerings vary widely from state to state, and they sometimes have restrictions on incentivizing fuel switching from gas to electricity. Within the nonprofit sector, community development financial institutions (CDFI) and energy efficiency-oriented nonprofits serve as the two primary funding sources for energy efficiency work.16 For more information on the role of CDFIs in climate change mitigation, see the Practitioners’ Guide to Community Lending for a Just and Equitable Energy Transition, authored in partnership by New York City Energy Efficiency Corporation (NYCEEC) and the Center for Impact Finance at the University of New Hampshire (UNH). Financing from banks to fill funding gaps may be available for qualified borrowers, but this form of funding can pose higher interest costs and sometimes sets high qualification standards.

Braiding various funding sources (both governmental and non-governmental) helps maximize the benefits and minimize the drawbacks of each individual source. In general, because low-income households may have limited resources to pay monthly debt payments, program administrators should endeavor to maximize the use of non-debt funding (grants and rebates) over debt (loans) for the program’s work.

When loans are incorporated into building energy upgrade programs, no-cost, low-cost, or forgivable loans are preferable, especially for low-income households that may not be able to budget for loan repayments.17 For more information on federal energy efficiency funding, please visit ACEEE’s “Putting New Energy Efficiency Incentives to Work.” American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE). “Putting New Federal Energy Efficiency Incentives to Work.” aceee.org/putting-new-federal-energy-efficiency-incentives-work#buildings. Another potential mechanism is “on-bill” financing, which employs a customer’s utility bill as a vehicle for repayment.18For more information about assembling the capital stack for residential retrofit programs, please see the ACEEE report “Retrofitting America’s Homes: Designing Home Energy Programs that Leverage Federal Climate Investments with Other Funding.” Figure 2: Participants in Emerald Cities Collaborative’s contractor academies.18 Emerald Cities Collaborative.

Section 3.4: Workforce development and economic inclusion

A skilled clean energy workforce is instrumental to scaling up building energy upgrade programs. Recruiting contractors and training workers from diverse backgrounds can also improve economic growth in underserved communities.

Building upgrade projects and programs are tangible ways to improve equitable access to opportunity, workforce diversity, and economic inclusion. As discussed elsewhere in this Playbook, R2E2 defines “economic inclusion” as a process that includes high-road employment and contracting opportunities and improved access to those opportunities for historically marginalized people and communities.

There is a growing demand for workers who can carry out building retrofit upgrades, driven by both private investment and new sources of federal and local funding. As additional funding becomes available, there will be increased demand for building upgrades, which require a skilled workforce to implement. Program administrators should anticipate needing access to a wide variety of professionals to carry out the building upgrades they hope to spur in their communities.

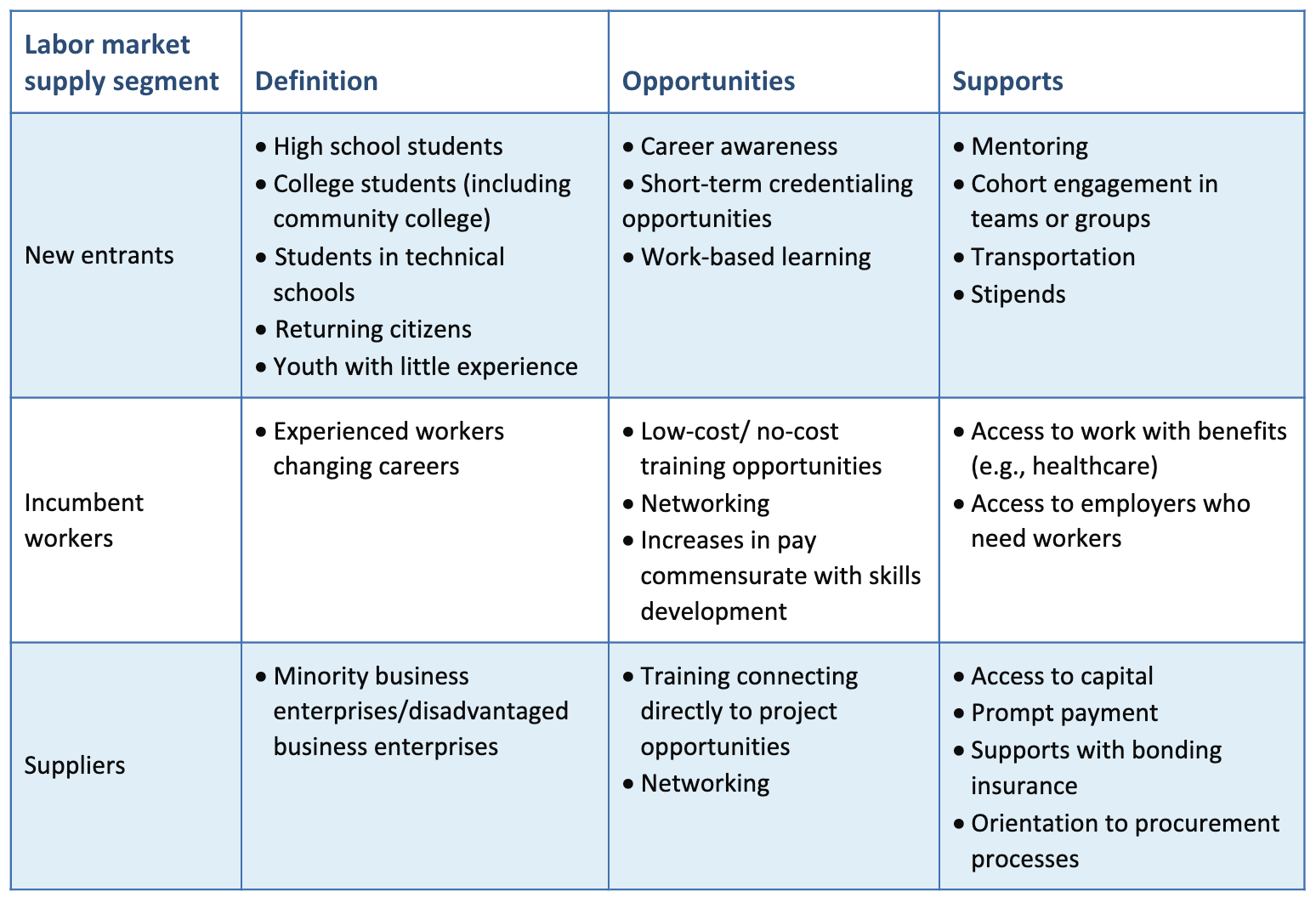

As demonstrated in the chart below, DOE offers four primary types of federal energy efficiency workforce development programs:

- DOE’s State-Based Home Energy Efficiency Contractor Training Grants reduce the cost of training contractor employees and provide testing and certification support.

- DOE’s Energy Auditor training grant programs train individuals to conduct energy audits or survey of commercial and residential buildings.

- DOE’s building training and assessment centers, and other career skills training programs, such as the Career Skills Training Program, establish training and assessment centers to identify opportunities for optimizing energy efficiency and environmental performance in buildings.

Figure 3: Federal funding for energy efficiency workforce development19 Mary MacPherson. 2023. “State and Community Energy Program Workforce Development Programs.” energy.gov/scep/articles/state-and-community-energy-programs-workforce-development-programs-webinar-slides.

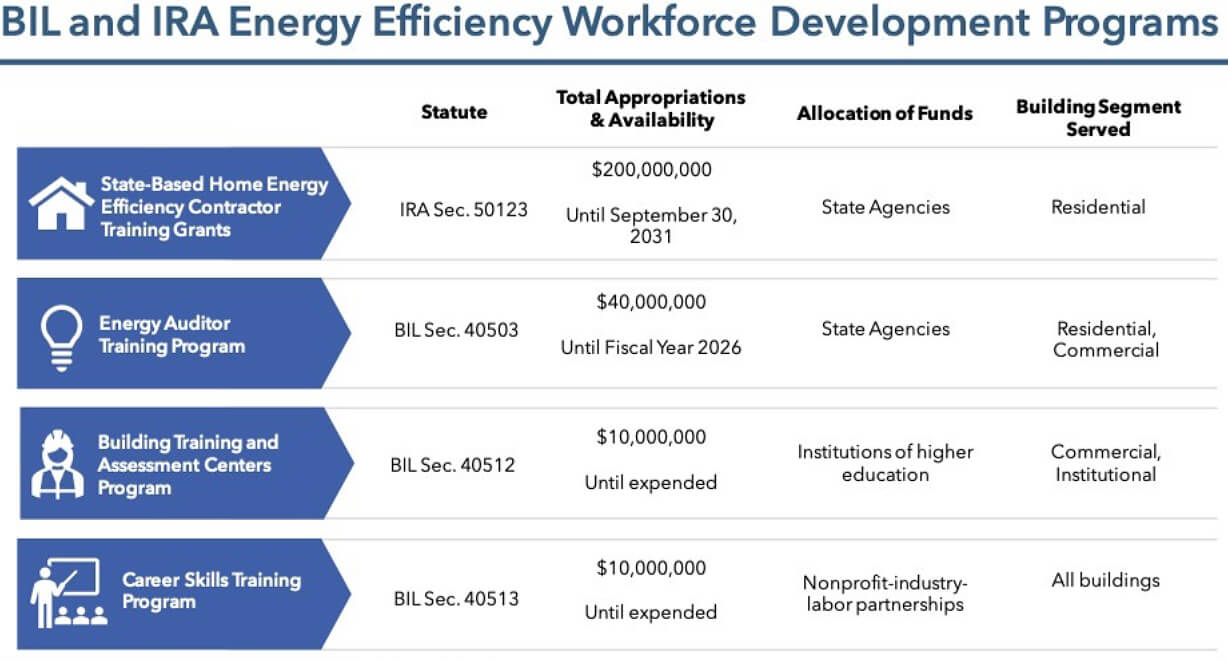

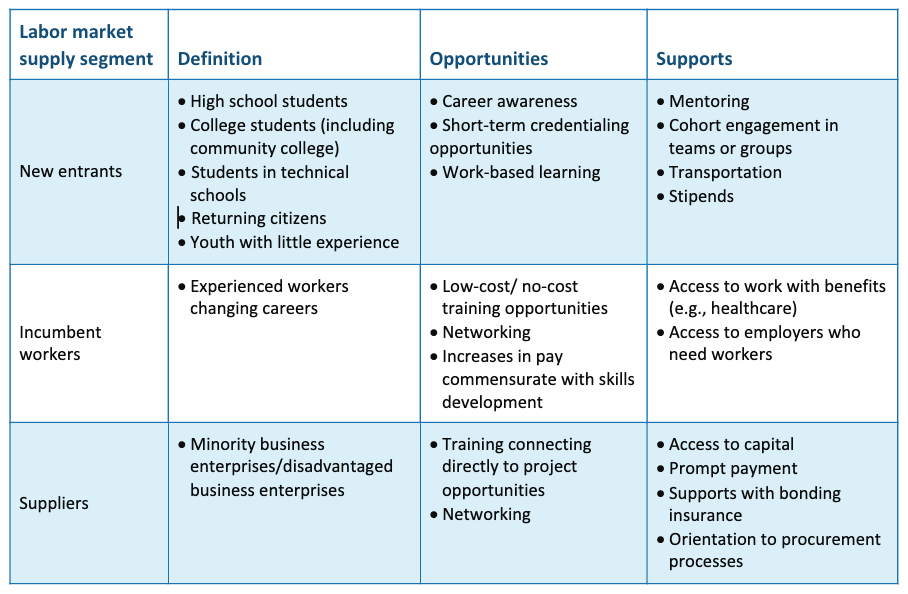

Workforce development opportunities can be approached with three main segments20Refers to the division of the labor market into separate sub-markets or segments, distinguished by different characteristics and behavioral rules. See: International Labour Organization. “Labour Market Segmentation” ilo.org/global/topics/employment-security/labour-market-segmentation/lang–en/index.htm. of the workforce in mind: new entrants, incumbent workers, and diverse suppliers. Engaging a diverse workforce requires project developers and implementers to understand each of these segments if they want to successfully retain workers.

Figure 4: Workforce opportunities

Figure 4: Workforce opportunities

Amid an increasing demand for workers, the greater lack of diversity in the labor market will require explicitly attracting, hiring, and retaining workers from marginalized groups. Some approaches to developing a diverse workforce are:

- Placing new entrants and incumbent workers into good-paying, high-quality jobs.21 We define ”good-paying” jobs as jobs that exceed the local prevailing wage for an industry in the region, include basic benefits (e.g., paid leave, health insurance, retirement/savings plan) and/or are unionized, and help the employee develop the skills and experiences necessary to advance along a career path.

- Investing in activities such as upskilling, credentials and certifications, work and learn opportunities, pre-apprenticeships programs, and partnerships with community organizations such as community colleges, YouthBuild/ Job Corps, unions, and community-based training organizations that are calibrated to the market’s demand for jobs in energy efficiency. 22 Short-term targeted training typically provided following initial education or training, and aimed at supplementing, improving or updating knowledge, skills, and competences. 23 A pre-apprenticeship is a program or set of services designed to prepare individuals to enter and succeed in a Registered Apprenticeship program. 24 YouthBuild is a competitive grant program that provides work experience, skills training, and educational services to eligible youth, with a focus on the construction trades. Job Corps supports a network of residential centers that provide intensive services for participants. Centers provide occupational training in a trade as well as appropriate academic and social supports. Jobs Corps has the highest funding of the three youth-targeted programs in WIOA.

- Weaving in both local and national programs to enhance proficiencies in specific areas, including Interstate Renewable Energy Council (IREC) training centers.25 IREC offers clean energy training for professionals in a variety of sectors, including firefighters, apartment maintenance technicians, and code officials.

- Requiring or incentivizing nationally recognized credentials from accredited organizations such as the Department of Labor’s Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act On-the-Job Training, Building Performance Institute (BPI Energy auditor), OSHA-10 and OSHA-30 Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) worker safety training, and the Consortium for Energy Efficiency (CEE) program for heat pump installation.

Program administrators can also take specific approaches to fostering economic inclusion in the workforce components of their building energy upgrade programs, including:

- Targeting programs to specific marginalized populations.

- Designing programs to ensure that the supply of new workers adequately matches the local workforce demand.

- Conducting disparity studies to provide a legal basis for creating local policies that promote economic inclusion or set metrics for economic inclusion.26 A disparity study assesses whether a government entity engages in exclusionary practices toward minority, women?owned, and disadvantaged business enterprises (MWDBE).

- Creating project labor agreements, workforce/community benefit agreements, and supplier diversity plans.27 PLAs are pre-hire collective bargaining agreements negotiated between construction unions and construction contractors that establish the terms and conditions of employment for construction projects. U.S. Department of Labor. “Project Labor Agreement Resource Guide.” dol.gov/general/good-jobs/project-labor-agreement-resource-guide.

- For example, Community Benefits Plans are legal agreements that are typically negotiated with the project developer, who agrees to fund specific benefits for local communities, which can include workforce training and metrics on economic inclusion. These have been used and promoted by DOE, among many other entities.

- Right-size contracts to help labor organizations or businesses develop their capacity.

- Unbundling projects to create right-size contracts can make projects accessible to contractors with different capacities. This can enable Minority, Women, and Disadvantaged Business Enterprises (MWDBE) to compete with contractors of similar size and capacity rather than competing against larger contractors.

- Pursue a “supplier diversity” strategy. This is a business strategy that focuses on creating a more-inclusive base of minority business enterprises.

- There are several resources that can help identify these businesses, such as labor management organizations, state or jurisdiction supplier diversity listings, minority or ethnic business contractor business associations or chambers of commerce, and community action agency weatherization assistance program administrators.

Click here to access Actions and Best Practices for Section 3

- 1For more information on how to approach equitable community engagement, see Section 1.1.

- 2For more information about designing successful residential energy upgrade programs, please see the ACEEE report ”Retrofitting America’s Homes: Designing Home Energy Programs that Leverage Federal Climate Investments with Other Funding.”

- 3Christopher Bloom. 2023. “June Is National Healthy Homes Month” NCHS Blog, May 31. nchh.org/2023/05/june-is-national-healthy-homes-month-2023/.

- 4Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2023. ” Most Recent National Asthma Data” cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm.

- 5Hayes, S., M. MacPherson, C. Gerbode, and L. Ross. 2022. Pathways to Healthy, Affordable, Decarbonized Housing: A State Scorecard. Washington, DC: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. aceee.org/research-report/h2201.

- 6Jonathan Wilson and Ellen Tohn. 2010-2011. “Healthy Housing Opportunities During Weatherization Work.” Golden, Colorado: National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Nrel.gov/docs/fy11osti/49947.pdf.

- 7Bratburd, Jennifer. 2021 “Increasing Access to Energy Efficiency: Options for Improving Weatherization Assistance.” MOST Policy Initiative. mostpolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/MOST_WX_report_2021.pdf.

- 8E4TheFuture. 2022. “Weatherization Barriers Toolkit” e4thefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/E4-EFG_Weatherization-Barriers-Toolkit-4-7-2022.pdf.

- 9WAP deferral is a widespread problem. A study from National Public Radio (NPR) found that in some jurisdictions, up to 60% of properties that are financially eligible for WAP are deferred from the program due to significant repair needs.

- 10Veena Singla et. al. 2018. “Making Affordable Multifamily Housing More Energy Efficient: A Guide to Healthier Upgrade Materials” energyefficiencyforall.org/resources/making-affordable-multifamily-housing-more-energy-efficient-guide-healthier-upgrade/.

- 11For more information on healthy building materials, see resources from Habitable, including resources on insulation product guidance and sealant product guidance.

- 12See Hayes and Christine Gerbode. 2020. “Braiding Energy and Health Funding for In-Home Programs: Federal Funding Opportunities” Washington, DC: ACEEE. aceee.org/research-report/h2002.

- 13One problem with tax credits, however, is that unless they are refundable they are less likely to be helpful to low-income families; a household must have a tax liability in order for it to be reduced.

- 14Formula grants are funding programs that an applicant does not compete for, though they must submit an application and meet other specified requirements. They ensure that designated recipients will receive funds and are usually administered and managed by state administering agencies. National Institute of Food and Agriculture. “Types of Federal Assistance” nifa.usda.gov/about-nifa/what-we-do/types-federal-assistance#Competitive.

- 15For more information on the IRA, please see ACEEE‘s policy brief on Home Energy Upgrade Incentives. Ungar, L., and S. Nadel. 2022. Home Energy Upgrade Incentives: Programs in the Inflation Reduction Act and Other Recent Federal Laws. Washington, DC: American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy. aceee.org/policy-brief/2022/09/home-energy-upgrade-incentives-programs-inflation-reduction-act-and-other.

- 16For more information on the role of CDFIs in climate change mitigation, see the Practitioners’ Guide to Community Lending for a Just and Equitable Energy Transition, authored in partnership by New York City Energy Efficiency Corporation (NYCEEC) and the Center for Impact Finance at the University of New Hampshire (UNH).

- 17For more information on federal energy efficiency funding, please visit ACEEE’s “Putting New Energy Efficiency Incentives to Work.” American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE). “Putting New Federal Energy Efficiency Incentives to Work.” aceee.org/putting-new-federal-energy-efficiency-incentives-work#buildings.

- 18For more information about assembling the capital stack for residential retrofit programs, please see the ACEEE report “Retrofitting America’s Homes: Designing Home Energy Programs that Leverage Federal Climate Investments with Other Funding.”

Section 3.4: Workforce development and economic inclusion

A skilled clean energy workforce is instrumental to scaling up building energy upgrade programs. Recruiting contractors and training workers from diverse backgrounds can also improve economic growth in underserved communities.

Figure 2: Participants in Emerald Cities Collaborative’s contractor academies.18 Emerald Cities Collaborative.

- 19Mary MacPherson. 2023. “State and Community Energy Program Workforce Development Programs.” energy.gov/scep/articles/state-and-community-energy-programs-workforce-development-programs-webinar-slides.

- 20Refers to the division of the labor market into separate sub-markets or segments, distinguished by different characteristics and behavioral rules. See: International Labour Organization. “Labour Market Segmentation” ilo.org/global/topics/employment-security/labour-market-segmentation/lang–en/index.htm.

- 21We define ”good-paying” jobs as jobs that exceed the local prevailing wage for an industry in the region, include basic benefits (e.g., paid leave, health insurance, retirement/savings plan) and/or are unionized, and help the employee develop the skills and experiences necessary to advance along a career path.

- 22Short-term targeted training typically provided following initial education or training, and aimed at supplementing, improving or updating knowledge, skills, and competences.

- 23A pre-apprenticeship is a program or set of services designed to prepare individuals to enter and succeed in a Registered Apprenticeship program.

- 24YouthBuild is a competitive grant program that provides work experience, skills training, and educational services to eligible youth, with a focus on the construction trades. Job Corps supports a network of residential centers that provide intensive services for participants. Centers provide occupational training in a trade as well as appropriate academic and social supports. Jobs Corps has the highest funding of the three youth-targeted programs in WIOA.

- 25IREC offers clean energy training for professionals in a variety of sectors, including firefighters, apartment maintenance technicians, and code officials.

- 26A disparity study assesses whether a government entity engages in exclusionary practices toward minority, women?owned, and disadvantaged business enterprises (MWDBE).

- 27PLAs are pre-hire collective bargaining agreements negotiated between construction unions and construction contractors that establish the terms and conditions of employment for construction projects. U.S. Department of Labor. “Project Labor Agreement Resource Guide.” dol.gov/general/good-jobs/project-labor-agreement-resource-guide.